On its 2008 album, Viva La Vida, British Band Coldplay sings of not wanting “to follow death and all of his friends”. The phrase even forms the alternative title of the album. But what exactly is our relation to death? And how, seeing as we all must die, do we not become one of his friends? Death, we know, warps our sense of the world. It leaves us who are left in its wake dispossessed, discomforted, lonely in our grief. It has a way, in Simon Critchley’s words, of “unstitch[ing] our carefully tailored suit of the self”.

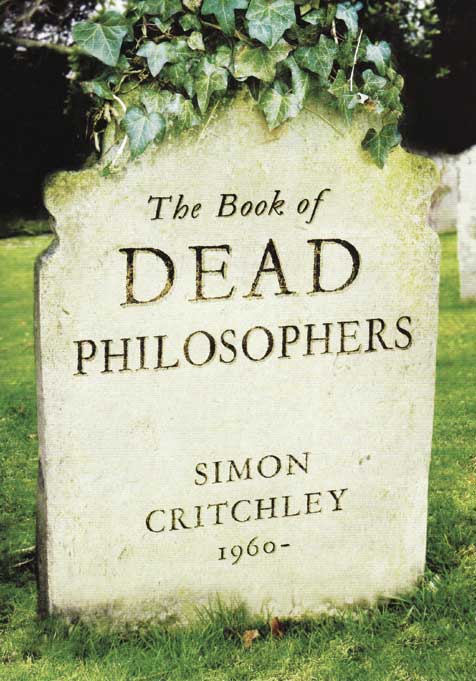

It is this troubling power of death that has inspired the investigations of Critchley’s recent book, The Book of Dead Philosophers. In it, Critchley sets out not to examine the abstract concept of death, nor just the ideas of philosophers who have since died. Rather, he examines the lives and deaths of philosophers, in their nobility or baseness: idealistic deaths and banal ones, the tragic and the ridiculous. He does so in the hope that, rather than expounding some new theory, it will produce a series of “question marks” over death, that serve as memento mori, post-it notes reminding us of our mortality and prompting us to seek to live more fully.

It is this troubling power of death that has inspired the investigations of Critchley’s recent book, The Book of Dead Philosophers. In it, Critchley sets out not to examine the abstract concept of death, nor just the ideas of philosophers who have since died. Rather, he examines the lives and deaths of philosophers, in their nobility or baseness: idealistic deaths and banal ones, the tragic and the ridiculous. He does so in the hope that, rather than expounding some new theory, it will produce a series of “question marks” over death, that serve as memento mori, post-it notes reminding us of our mortality and prompting us to seek to live more fully.

But why should we need such reminders? Thoughts of death are at once all too infrequent, and yet strangely all too encompassing for us. We have succeeded in banishing death from our lives. Death is sent to live in sterilised institutions, and is sanitized by means of bright neon lights and potpourri. Death has become for us “all or nothing”. It is the absolutely last thing. And so we grasp at eternity but only cheapen life in the process, and only consider death with thoughts of horror. We refuse to entertain death in our thoughts, and in return, it rules our lives like an invisible king.

Critchley explains this situation by pointing out that Western societies are “experiencing a deep meaning gap that risks broadening into an abyss”. The gap is with regard to what it means for one to be an individual self, and collectively, to be a society. We are, Critchley suggests, utterly confused here. It sends us running all too often after shallow solutions, advertised with lights, glitter, and expensive price tags. We are after certainty, and “what this desire for certainty betrays,” Critchley thinks,

| is a profound terror of death and an overwhelming anxiety to be quite sure that death is not the end, but the passage to the after-life. True, if eternal life has an admission price, then who wouldn’t be prepared to pay it? |

All too often though, our desire for certainty can be abused by people seeking to profit from it, offering superficial and short-lived solutions that only leave us more anxious than before.

The Book of Dead Philosophers is critical of a superficial religion that feeds off the fear of death. But on the other hand it is also very critical of the ‘philosophical’ kind of death that feels no fear or trouble or is even contemptuous when it catches sight of its end. Indeed, the book—though it is about philosophers—is not a very philosophical book at all. ‘Philosophy’ all too often entails contempt of the personal and messy details of life. But Critchley pursues the lives and deaths of men and women from Thales to Derrida with enough wit and humour to keep the reader with little interest in philosophy enthralled. You will, I wager, die laughing.

This delicate balancing act, between contempt for death and absolute fear of it, finds expression from Critchley in a surprising place. Though he is not otherwise interested in Christianity, Critchley expresses a great admiration for many thinkers in the Christian tradition for the way in which they entertained death. He considers Paul, Augustine, Gregory of Nyssa and others, and is amazed by the rigour of their lives, thoughts, and attitudes to death:

| To put the central paradox of Christianity at its most stark, Christ puts death to death and in dying for our sins we are reborn into life. To be a Christian, then, is to think of nothing else but death (82). |

Critchley seems astonished at this. Death from an authentic Christian standpoint is a harrowing path that must be traversed in order to receive life in its full. But such a passage prompts Critchley to wonder, “how many so-called Christians are really Christian?” That is, he finds it hard to believe that most of those he sees around him who profess to be Christian actually live up to this task. The challenge to Christians here is stark:

| “Nothing is more inimical to most people who call themselves Christians than true Christianity. This is because they are actually leading quietly desperate atheist lives bounded by a desire for longevity and a terror of annihilation” (280). |

Critchley rightly sees that true Christianity does not entail an overweening quest for longevity, worldly goods or power. Rather, a full engagement with life that nonetheless holds on to a sense of the eternal to provide perspective and direction with which to face both life and death.

Critchley seems to follow the lead of French philosopher Jacques Derrida here. For Derrida, as in the Christian tradition, life and death are intimately intertwined, and defy neat separation.

Since Plato it has been held that to be a philosopher is to learn how to die. And this is part of Critchley’s task—to teach us to face death. For Derrida, though he does not disagree, he refuses to be educated on the subject, he will not give himself over to it. “I believe in this truth without being able to resign myself to it. And less and less so. I have never learned to accept it.” The horror of death remains for him, and he says he is “uneducable when it comes to any kind of wisdom about knowing-how-to-die”.

For Derrida, death remains just plain awful, and in this sense he shares a connection with Christianity where death remains the great enemy of life

For Derrida, death remains just plain awful, and in this sense he shares a connection with Christianity where death remains the great enemy of life. For Jesus, death arouses revulsion, and anger. As Jesus stands before the tomb of his friend, Lazarus, four days dead, he literally snorts in anger and disgust at death.

Critchley’s book encompasses a tenet of the teaching of Jesus on the subject of death. We are enslaved by the fear of death. It becomes our ultimate reference, and this has profound consequences for the way we live—paradoxically, the attempt to hide from it only extends its power over us. It can lead us to cling on to fleeting pleasures, all the while showing a contempt for life, in the sense that we refuse to accept its conditions. “The only priesthood in which people really believe”, says Critchley as he levels with us, “is the medical profession and the purpose of their sacramental drugs and technology is to support longevity, the sole unquestioned good of contemporary Western life” (279).

The principle is illustrated in an alarming way in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, which, despite its children’s literature garb, forms a profound and lengthy meditation on death. The scornful, murderous, humourless Lord Voldemort is animated by the pursuit of immortality. His self-given title means flight from death. But, as the story reveals, Voldemort’s flight from death only leads him to enshrine it as the supreme power, rendering him incapable of love, and contemptuous of life.

We need, in Dietrich Bonheoffer’s words, therefore, to allow to death its “limited rights”. To “neither cling convulsively to life, nor cast it frivolously away”. To accept life and what it offers; good and evil, trivial and important, joy and sorrow. But how to do this? For Critchley, it seems the Christian gospel holds out an attractive hand for this task—one that even many of those who profess to be Christians need to revisit: a serious contemplation of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection, in order to break free of enslavement to death. It may well be that in that contemplation, we learn not to follow, but to overcome the enslavement of ‘death and all his friends’.

Drew Dunstall is a CPX fellow and a PhD candidate in the Modern History and Philosophy Departments at Macquarie University, Sydney. His research covers the work of Jacques Derrida and its relation to the philosophy of history.