It comes as a surprise to most people to learn that the attendance record of the Melbourne Cricket Ground has been unbroken for almost sixty years. Despite a succession of Boxing Day tests, Grand Finals, and touring superstars, never has the 130,000-plus crowd that gathered on a Sunday afternoon in 1959 been surpassed.

More surprising, certainly, is the thing that drew them: an open-air church service. Hymn-singing, prayers, testimonies, and the climax – a sermon by a visiting American evangelist calling Australians to be turn back to God for forgiveness and new life.

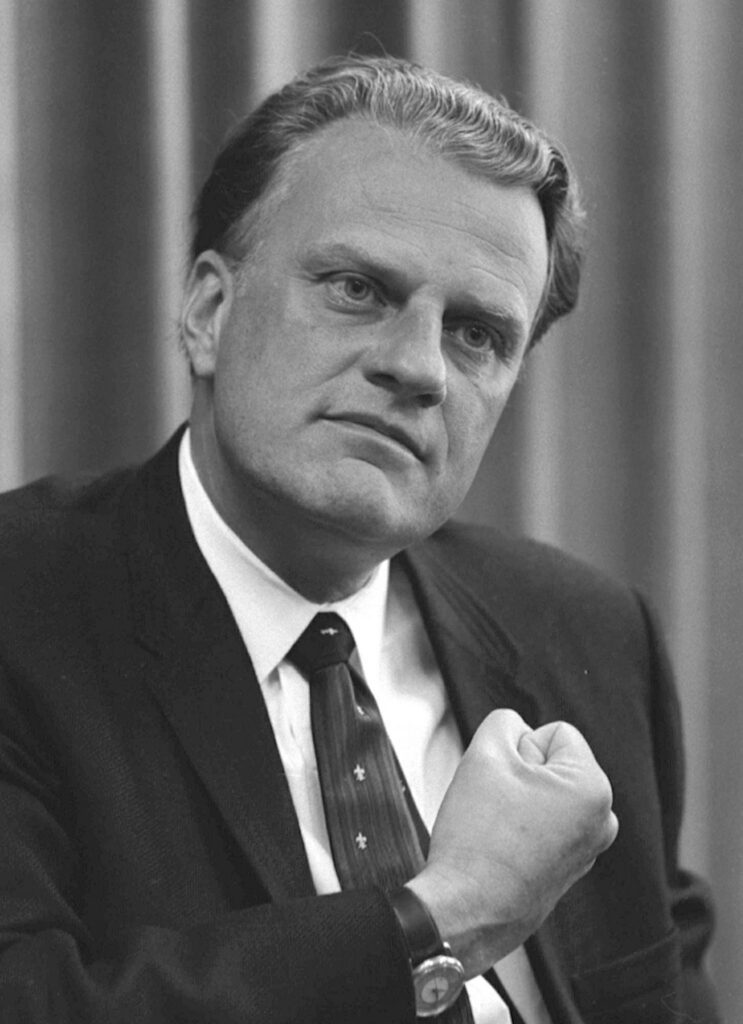

That evangelist was Billy Graham, whose death last Wednesday at the age of 99 has been reported around the world. As pastor to presidents and – having preached in person to over 200 million people in 185 countries (plus countless more through television) – arguably the most globally significant evangelist ever, it is hard to deny his religious and cultural influence on the twentieth century. Indeed, while the news of his death would be greeted by most under 40 with a bemused “Billy who?”, thousands of Australians have also been influenced by the man and his message. Graham got under our skins.

The three Australian Graham “Crusades” – 1959, 1968-9 and 1979 – were, by all accounts, a big deal. Thousands gathered in stadiums to hear and see him, politicians and civic leaders offered effusive support, and even the press, after initial scepticism, were on Graham’s side.

In 1959, the record crowds in Melbourne were repeated around the nation over Graham’s three months here, with aggregate audiences exceeding 3.5 million. 130,752 people, roughly 1.24 per cent of the population accepted Graham’s invitation to put their faith in Christ, to be ‘born again’.

Stories of remarkable (and lasting) individual transformations abounded. Graham’s message also seemed to make its mark on our life together, with statistics on crime, alcoholism, and extra-marital births (this was, of course, before the pill) all plateauing in the few years following his 1959 visit.

Looking back on the Graham phenomena from our own vantage point, the old adage seems to ring true: “The past is a foreign country. People do things differently there.” It feels so distant, so quaint, a phenomenon. Many will no doubt raise their eyebrows and repeat the same critiques always made of the response to Graham’s invitation: emotionalism, mass marketing, individualism, and so on. And some will welcome the fact that the phenomenon is well past. Still, something happened when he preached that is hard to dismiss. Graham got under our supposedly secular skins.

The questions Graham raised about our deepest problems and strongest yearnings have not gone away.

Even today, Billy Graham turns up in surprising places. He was introduced to a new audience of millions through the second season of Netflix’s epic The Crown. Visiting London for a crusade in 1966, he was invited by the Queen to preach in Windsor Castle, impressed as she was by his “rather handsome” features and “wonderful clarity and certainty”.

In an exchange over tea afterwards, we see the self-described “simple Christian” Elizabeth seeking spiritual counsel from Graham. She asks how she, driven by duty, can come to forgive her uncle, the former Edward VIII, for his wartime collusion with the Nazis. Graham responds: “Dying on the cross, Jesus himself asked the Lord to forgive those that killed him.” According to Graham, being able to forgive others starts, unexpectedly, “in asking for forgiveness oneself”.

Whether the conversation ever happened we’ll never know. Yet Graham’s warm and clear words to a conflicted monarch were of the same essence as every sermon he preached. He would speak to people about their spiritual hunger and thirst, the burdens they were carrying, their yearning for security and peace. He would speak to them about Jesus.

While our cultural and moral landscape has changed irrevocably since the heyday of Graham’s crusades, seemingly confirmed by the growing adherence to “no religion” in census returns, the questions he raised about our deepest problems and strongest yearnings have not gone away. Reactions to the Barnaby Joyce affair suggest that there are deep moral feelings about right and wrong, judgement and forgiveness, and the primacy of relationships sitting not far beneath our putatively relativist, secular skin.

As we tire of the empty promises of consumerism and the Botox-like call to “the power of positive thinking”, the message of that “old-time religion”, seemingly so foreign, has a strange relevance. The MCG has long since returned to its more familiar role as a secular temple, but Graham’s message continues to intrigue, surprise, and change lives in unanticipated ways.

Dr Hugh Chilton is a Conjoint Lecturer in the Faculty of Arts and Education at the University of Newcastle, Director of Research and Professional Learning at The Scots College, and a CPX Fellow. He is Vice-President of the Evangelical History Association and his first book, Evangelicals and the End of Christendom: Religion, Australia, and the Crises of the 1960s (Routledge) is due out in 2018.