In 2011 children’s author Frank Cottrell Boyce’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again breathed new life into a cherished old story. In the latest version the magical vehicle is a broken down old camper van that flies the Tooting family to fame, if not fortune, rescuing them from serious scrapes and propelling them to remarkable adventures in exotic locations like Egypt, Paris and Madagascar.

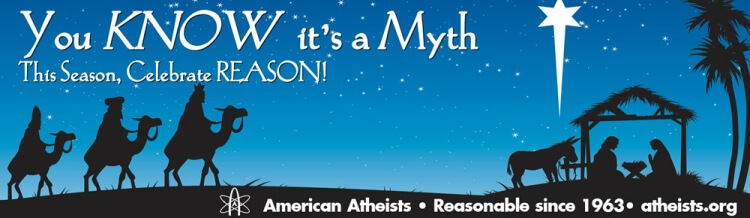

I can see my seven year old just wishing with every part of himself that the story be true, but deep down knowing it’s just a fantasy. Perhaps that’s the sentiment that was on display a few years ago when an atheist group in the U.S. purchased a billboard ad at the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel in New York. The billboard showed a nativity scene with three men on camels riding towards a manger, a bright star overhead. The text read, “You KNOW it’s a Myth—This Season, Celebrate REASON!”

A ‘sign’ of enlightened thinking perhaps, but the idea is not new, and those responsible for the billboard ride on the shoulders of some formidable opponents of religion who regard it as a human construction emanating from our deepest fears, hopes and dreams. Various permutations of this notion gained popularity from the 19th century onwards when Ludwig Feuerbach posited that God was the product of human wishes.Others ran with that, giving their own slant to essentially the same idea. God is the substitute for living a life of drudgery in a factory while others get rich (Karl Marx), a projection of repressed desires and disappointment with our Dads (Sigmund Freud) and a symbol of human potential (Erich Fromm). “In every wish we find concealed a god, but in or behind every god we find nothing but a wish,” wrote Feuerbach.

“What is it that people wish for more than anything else?” asks French philosopher André Comte-Sponville. His answer: We don’t want to die. We want to be united with lost loved ones. We long to be loved unconditionally and for justice and peace to triumph. Religion and especially Christianity promise all that, says Comte-Sponville, but like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, it’s too good to be true.

So is it merely a human fantasy that lies at the heart of the original Christmas event?

This whole ‘religion as a human construction’ sounds potentially devastating for believers until you realise that something can be both a human projection and a reflection on reality at the same time.

American sociologist Peter Berger illustrates this with an example from mathematics. Humans project out of their consciousness mathematics that somehow corresponds to a mathematical reality external to them, and which their consciousness appears to reflect. Berger argues that this is possible because “man himself is part of the same overall reality” and that “there is a fundamental affinity between the structures of his consciousness and the structures of the empirical world.”

Berger suggests that the same may be true of the projections of humanity’s religious imagination.

It’s not unreasonable to think that some self-interest could play a part in a decision to consign God to the status of imaginary friend.

Australian author Robert Banks explores this question in his latest book And Man Created God: Is God a human invention? He acknowledges the human tendency to fashion gods in our own image and cautions religious believers to heed the warnings of the Freuds, Fromms and Feuerbachs.

But Banks draws on the work of C.S. Lewis to argue that the general wishes of humans—such as an infant wanting food, a lover wanting sex, a person longing for knowledge, (or for Manly to win the premiership) all have counterparts in the real world. Therefore, it’s a fallacy to suggest that the desire for something to be true necessarily counts against its validity.

Banks also notes that this cuts both ways. Disbelief in God could just as easily be a form of wish fulfilment as belief. After all, religious commitment has the inconvenient habit of challenging desires, demanding personal change, and requiring commitment to a community comprised of a mixed bag of punters—many of whom you might otherwise choose to avoid. It’s not unreasonable to think that some self-interest could play a part in a decision to consign God to the status of imaginary friend.

As another year rolls around we get ever-diminishing glimpses of the strange and ancient Christmas story, now so commercialised as to be barely recognisable. It’s the story of an obscure birth in an out-of-the-way place. A child born in shameful circumstances among straw and mud and poverty, who also, so the story goes, happens to be ‘God with us’, the one who was present at the laying of the foundations of the universe. Is it a story that has any currency these days?

I’m writing this from the children’s hospital in Randwick where I’ve been for over a week with my sick daughter. It’s a sobering place. Some kids arrive with relatively minor complaints, and leave soon after. Others endure multiple operations and excruciating pain drawn out over months. And then there are the cases that you know won’t end well. Parents of these children have given up meeting your eye. They carry with them an inexpressible sadness. This is the world we live in.

But Christmas morning reminds us that there is a promise that one day there will be a world of no mourning or crying or pain or children needing lumbar punctures or CAT scans. And so those in the West who still celebrate Christmas will do so with a profound sense that this day represents a moment of hope that, perhaps despite appearances to the contrary, God is real, and that he cares enough to get intimately involved in the human drama.

There are still enough nativity plays on at this time of year to suggest that lots of people think of the Jesus story as an important one to hang on to—for the kids. But it’s worth noting that adults read and remember kid’s stories with a child-like longing that they be real. The wish for happy endings, miraculous escapes, punishment of wickedness and saving of the innocent; of places where evil is conquered, justice restored and where death is not the end. These are things that never quite leave us.

It’s possible that the belief down through the centuries of the majority of people, that there is a God who creates and sustains the universe, could be an immature fantasy out of which we are slowly emerging. But I’m left wondering whether those who dismiss outright the Gospel accounts as myth ever wonder whether this “story for the kids” might also be true; whether it has anything more than sentimentality to offer us as we navigate life’s big questions and struggles.

Simon Smart is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity

This article originally appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald.