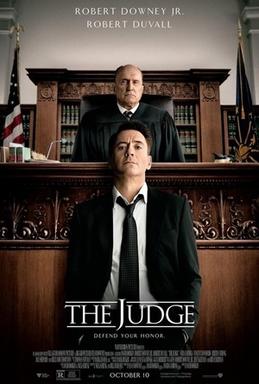

Even those who travel across the world to escape their upbringing rarely can shrug off the emotional connection to their family – for all the damage done, there are always ties that still bind. In David Dobkin’s The Judge viewers are exposed to family dysfunction that is likely to have a familiar ring to anyone who has ever felt a stirring of anxiety at the thought of heading ‘home’ for a family get-together.

When Chicago lawyer Hank Palmer (Robert Downy Jnr.) returns to Carlinville Indiana, the country town he grew up in, to attend his mother’s funeral, he hasn’t been back for many years. A traumatic event in his teenage years has kept him away and now as a slick and successful but morally compromised defence attorney, his hometown feels suffocatingly small.

But his true source of dread springs from the inevitable confrontation with his father, Joseph Palmer (Robert Duvall), the town’s judge. The heart of this story is found in the seemingly intractable conflict between them. The relationship is difficult enough but when Hank has to defend his father in court after the Judge is accused of a hit-and-run murder, family tensions explode.

This is almost a really good film. The establishing scenes are alarmingly predictable. The wild boy returns after years away, and—ah yes, here comes the childhood sweetheart, still in town, still beautiful and still single, having never really gotten over him. And, of course, this is where he falls off his old bike on a country road and she just happens to be driving past to pick him up. Once the rather clunky orientation is complete the story becomes more engaging.

An estranged son coming home from the city to reconnect with a stubbornly severe father is clearly not an original plot, but it remains timelessly interesting. Duvall and Downy Jnr sparkle with rhetorical flourishes and lines delivered with precision and flair, the atmosphere of the courtroom providing a fitting environment for them to parade their skills. What turns out to be a quality courtroom drama is made even better by the presence of Billy Bob Thornton as prosecuting attorney.

An unyieldingly hard old man, the Judge’s rare displays of warmth are directed towards anyone but his black sheep son. The distance between them is deep and damaging and toxic. But the shadow of illness that hangs over the Judge leads to more tender moments as father and son together face the old man’s mortality and growing vulnerability.

Some might find these elements of the story overly sentimental, and there is a lack of subtlety here that plagues so much of what Hollywood produces. But despite that, an examination of the complexities of family relationships, especially in the hands of such accomplished actors, is rewarding. There is potency to any story that mines the absent love of a father and the craving of even adult children for their father’s approval. Downey Jnr’s portrayal of that dynamic is convincing and moving.

In his book The Stories we Tell – How TV and Movies Long for and Echo the Truth, Mike Cosper says that if art is accurately portraying life it will reflect brokenness and the heart’s longing for eternity, beauty and redemption. Cosper believes that the modern stories we tell will frequently intersect with, reflect and parallel key aspects of the grand story of the Bible.

In The Judge there are echoes of the returning prodigal son of Luke’s gospel. The dramatic tension of the ancient story pivots around the love of a father that’s undeserved but desperately sought. The shockingly lavish welcome offered to the rebellious boy is intended to tell us something about what God is like—that he is overflowing with unconditional love for even the children who have rejected him.

There is a longing attached to that story that is universally understood. Whether we are fathers ourselves or have had a father, or even if we haven’t, we all know the profound significance of the role and how far short everyone falls in performing it.

Perhaps the undoubted ache we all experience when contemplating this topic is somehow a reflection of our longing for redemption for the wounds we have suffered but also inflicted. In a mysterious way this is what leads many to seek the ultimate father—the one Augustine said is, when we are estranged from him, the source of all our restlessness. If so, that would explain why stories like The Judge, even when imperfectly told, continue to hold such rich emotional power.

Simon Smart is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity.