In 1959 American preacher Billy Graham came to Australia in what proved not only the most important religious event in Australian history but has been called the most successful evangelistic endeavour in the history of the world.

According to records, 3,362,240 people – nearly a third of the 10 million population of Australia at the time – attended the live rallies over four months in eight Australian cities, plus three in New Zealand, and many more heard him on radio or broadcast into churches around the country.

Macquarie University historian Stuart Piggin says 1.24 per cent of the Australian population – more than 130,000 people – accepted Billy Graham’s invitation to become a Christian. His final Melbourne rally set the MCG record attendance of 143,000 and his final Sydney rally set the then Sydney record of 150,000, crammed into both the Sydney Cricket Ground and Sydney Showground.

Billy’s son Franklin was a small boy in 1959, when Billy was away for nearly six months. “I remember when he came back none of us children recognised him, and it hurt him. My mother claimed I came down to their bedroom early in the morning, came to her side of the bed and asked who that strange man in bed with her was.”

This month Franklin Graham, long a noted evangelist himself, begins a 60th anniversary six-city tour of Australia, visiting Perth, Darwin, Melbourne (at the Hisense Arena next Saturday), Brisbane, Adelaide and Sydney. He will be preaching precisely the same message, he says, but there are fascinating contrasts today in both the nation and the evangelist.

It is inconceivable that any visitor in any arena could have the impact today that Billy Graham had in 1959. Further, Billy Graham was one of the most admired Americans of the 20th century, hailed by president George W. Bush as “America’s pastor” – the mostly apolitical confidant of every US president from Harry Truman to Donald Trump. He preached live to some 215 million people in his 99 years, which ended in February last year.

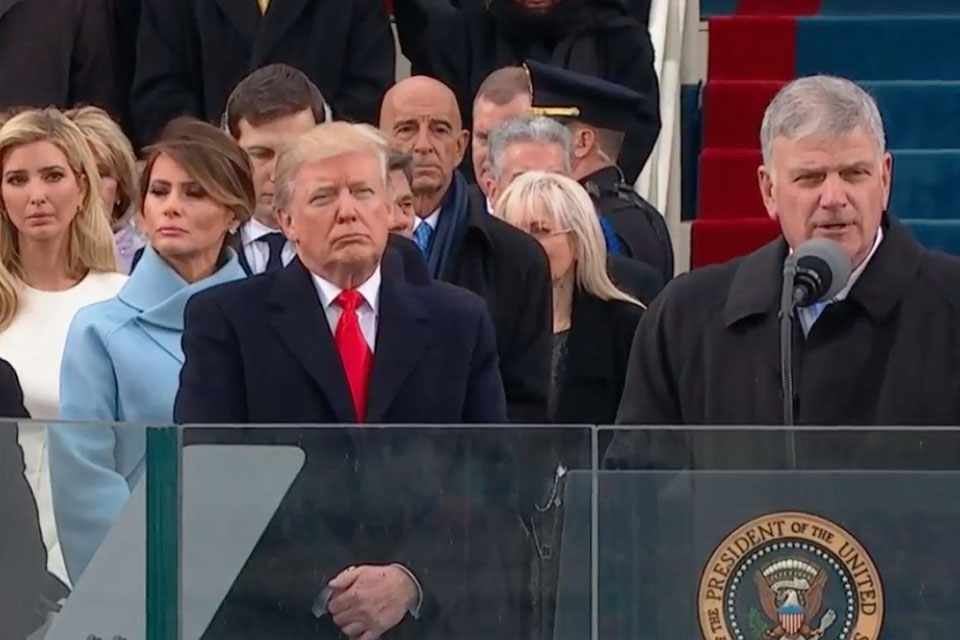

Franklin Graham is vastly more controversial because of his strong support for Trump and his uncompromising tone. As American Baptist leader Russell Moore put it, the problem with Franklin Graham is that “the Religious Right turns out to be the people the Religious Right warned us about”.

Melbourne Anglican theology lecturer Michael Bird has already written that he will not attend the rallies because of what he calls “Graham’s idolatrous devotion to Trump – the way he has messianised Trump to look like Jesus and caesarised Jesus to look like Trump” (Caesar symbolising political power in New Testament times).

Two social factors helped Billy Graham’s incredible success in 1959, Piggin says. First was the Cold War, which caused considerable fear, and second was the widespread conviction that Australia was declining morally.

Piggin studied contemporary statistics relating to crime and morality, and found massive increases in assault, burglary and births outside marriage in the 1950s and ’60s, but a short hiatus after Graham’s Crusade. Even nationwide beer consumption fell 10 per cent in the year after, he says: “There was a widespread longing for religious revival, not only in the churches but the community as a whole, which is interesting – it seems to mean people understood what revivals of the past were and were aware of them. They probably aren’t any more.”

The Age in 1958 opined that the population was “hoping for a genuine revival such as those of the past”.

Evangelical Christianity in Australia up to that point was very pietistic, very self-absorbed, and Billy wanted people to get out there.

World War II was not long past, so many Australian church leaders thought in military terms, and were warrior-like in their prayers and expectations, Piggin says. Another important factor is that the crusade was incredibly well organised, intentional and precise. There were 11 subcommittees, all run by Australians.

And not least, Graham was at the height of his powers in 1959. He became a world figure at the Los Angeles crusade in 1949, did very well in London in 1954, better in New York in 1957 and better still in San Francisco in 1958. But 1959 was the first crusade that covered an entire country, with the involvement of almost all Protestant churches and no dissent.

Piggin has watched all the sermons Graham preached in Australia at the Graham archives. “It was certainly fantastic preaching, very well done. It wasn’t terribly emotional, but it was very well constructed to achieve an end. He first went for comprehension, then conviction, then an appeal so you were asked to do something, make a confession, commit your life to Christ.

“And that was important because evangelical Christianity in Australia up to that point was very pietistic, very self-absorbed, and Billy wanted people to get out there. At that final meeting at the MCG, he preached on the text ‘occupy until I come‘. It was all about don’t just sit around and wait for Christ to come but get involved, go back to your churches, your workplaces, your schools.”

Graham certainly had charisma: tall and handsome, urgent and passionate, totally confident. A woman quoted in a 2009 Compass documentary said: “Our hearts were fluttering for Billy Graham. He was such a sexy-looking man. Most of the ministers we’d had were just very plain, everyday, older men. And here was this young man, a beautiful man, telling us all these wonderful things. It was just a revelation.”

Franklin Graham may not have the same charisma, but he has the same passion and conviction. Graham, chairman and CEO of both the Billy Graham Evangelical Association and the international aid organisation Samaritan’s Purse, had by last year preached at 184 evangelistic festivals in 49 countries since 1989.

What is he expecting in Australia?

“Of course the need of the human heart is the same. People are searching, and turn to drugs or sex or various religions or whatever trying to find answers to life, and I’m coming to preach the same gospel message my father preached, and giving an invitation to put their faith and trust in Jesus Christ.

The gospel message, Graham says, is that God sent his son Jesus Christ to earth in the form of a man to take the sins of the world.

“I’m looking forward to it, hoping that many people will put their faith in Christ. We’re not taking up offerings, we’re not asking for money, we’re here to give in Jesus’ name.”

The gospel message, Graham says, is that God sent his son Jesus Christ to earth in the form of a man to take the sins of the world. “And when Jesus Christ hung on the cross he shed his blood for the sins of every human being, and if we are willing to turn from our sins and accept that by faith, then God will forgive our sins and heal our hearts and Christ will come into our life.”

Asked about his support for Trump, Graham has the practised ease of someone who has answered this scores of times. He didn’t campaign for Trump, he says (although critics say his 2016 Decision America tour of all 50 state capitals amounted to precisely that, and along with Jerry Falwell junior he is credited with helping persuade 80 per cent of white evangelicals to vote for Trump).

“But now that he is President it is important that we try to support our leaders, no matter what kind of people they are,” Graham says. “The American people voted for him, and of all the presidents I have known he has been the most friendly to Christians. He is the first President in our country that is not a politician – he says what he thinks. Does he have faults? We all do, we have all failed, and it’s important to pray for our leaders whether we agree with them politically or not.”

The Apostle Paul explicitly rules out doing evil to bring about good. In supporting a man who has reportedly told nearly 10,000 lies since taking office, who boasted of his sexual assaults, who demeans his opponents, is Graham not doing this?

He replies: “In the scriptures Caesar was the ruler of the world, and he was a ruthless person who killed who knows how many hundreds of thousands of people. But at the same time, the Bible says all authority on earth has been given by God, so for some reason God has allowed Donald Trump to become President of the United States.”

This doesn’t satisfy such critics as Bird, who wrote last year that Graham had used Christianity as a political prop to sanitise Trump despite his “egregiously non-Christian character and the dubious moral quality of many of Trump’s policies”.

“Franklin Graham’s Christianity is thoroughly implicated in a particular political vision, a peculiar agglomeration of policies about America’s place in the world; it is tied to a troubling form of pugnacious nationalism, centred on the anxieties of the white middle class, and seeks political influence at the expense of faithfulness to the gospel. Graham’s god looks like an apotheosised version of Ronald Reagan; his Jesus comes with an endorsement from the NRA; and his Holy Spirit is the presence of American military power in the world.”

Bird cites the apparent hypocrisy of Graham calling on then president Bill Clinton to resign over his affair with Monica Lewinsky, but explaining away or calling irrelevant Donald Trump’s philandering and boasts of sexual assaults. He also accuses Graham of blending Trumpism and Christianity in a “Faustian pact” of political support for preferential treatment, and fears this will reflect badly on Australian evangelicals, suggesting they are pining for an Aussie version of Trump.

In reply, the Billy Graham and Samaritan’s Purse chairman in Australia, Karl Faase, sought to pour oil on troubled waters. He wrote in Eternity, a Christian newspaper: “I have heard Franklin Graham speak at events such as these around the world, and have seen God use him to bring thousands to a saving knowledge of Jesus. I am confident that the events being planned across Australia in 2019 will be marked by three key qualities: a clear gospel message, a series of fabulous meetings and a politics-free agenda.”

Politics affected Billy Graham as well. He returned to Australia in 1968 with much less impact, though still attracting large numbers and reaching many people. What happened in the intervening years? Vietnam, says Stuart Piggin. Billy Graham refused to condemn the war, which upset many Australian Christians.

It will be harder now, Piggin adds: “In 1959, the default was towards Christian values. In every small community in Australia you had four churches – Methodist, Presbyterian, Anglican and Catholic – so until the 1970s Australia was one of the most Christianised nations on earth in terms of values.

“Nowadays, in contrast, a lot of people in Australia think that Christianity is dangerous, it’s pernicious, you don’t need to send your kids to Sunday School, you need to keep them away from Sunday School.”

Besides apathy, an anti-Christian secularism is rising.

Christians are no longer the home team but the away team, and this will become increasingly evident.

One of Australia’s highest-profile Anglicans, former Sydney archbishop Peter Jensen, was converted at Billy Graham’s Sydney rallies.

The world-view changes since 1959 have been revolutionary, Jensen says. Christians are no longer the home team but the away team, and this will become increasingly evident. All community groups and clubs, indeed the family, have suffered decline because of the triumph of individualism.

But Jensen doesn’t think that means Graham’s 2019 tour cannot succeed.

“Since Billy Graham preached the true gospel in the power of the Spirit, and since the Lord was of a mind to bless us, our nation was shaken. In a sense it had nothing to do with the times – it was a spiritual moment which you cannot predict or create. I believe that it could happen again in our very different time, because God is God and we were no better back then.”

Barney Zwartz, a senior fellow for the Centre for Public Christianity, was religion editor of The Age from 2002 to 2013.

This article first appeared in The Age.