A new parliament has seen the resumption of hostilities over Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

And while newly elected politicians go over old ground – free speech and political correctness, the right to be free of bigotry or the right to be a bigot – the conversation we’re having serves to highlight the kinds of conversations we’re not.

Australia, along with other Western democracies, has made great strides away from both institutional and casual racism over the last half-century. But all the evidence suggests that a deep undercurrent of ugliness remains. It surfaces in episodes from the mass bullying of Adam Goodes last year to the revived electoral fortunes of One Nation: the deeply ingrained racism that was integral to colonisation is still with us.

The daily experience of minorities – racial, ethnic, religious, sexual – far too often doesn’t match our rhetoric about diversity, multiculturalism and equal opportunity. Real people continue to come up against a wall of prejudice that many of us want to believe was broken down long ago.

Why the disconnect?

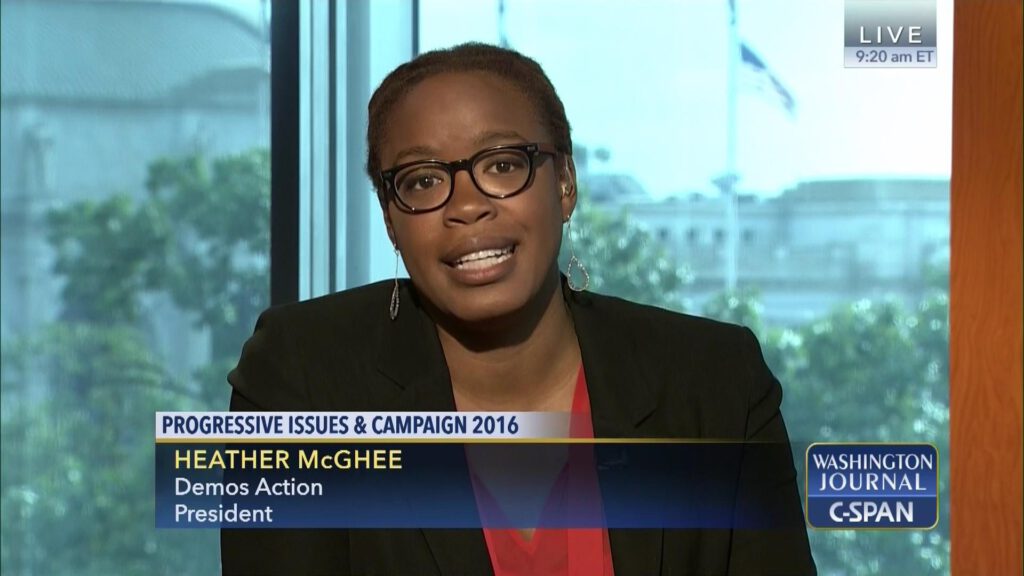

Here’s an example of a conversation about prejudice and tolerance that we’re emphatically not having. It took place recently on an American political program, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal. Guest Heather McGhee, the African-American president of public policy organisation Demos, took a call from Gary, from Fletcher, North Carolina.

“I was hoping that your guest can help me change my mind about some things,” says Gary to the host of the program (and, apart from him, no one ever on a talk show before this moment).

“I’m a white male, and I’m prejudiced. It’s not something I was taught, it’s something I learned – when I open up the papers, I get very concerned about what young black men are doing to each other … I have these fears. And I don’t like to be forced to like people, I like to be led to like people, through example. What can I do to change – to be a better American?”

You can tell, watching the interview, that this is probably not a question that McGhee has ever had to field before. But her answer is a model of graciousness.

She thanks Gary for his honesty, and for opening up this conversation. She notes that, actually, we all have fears and prejudices towards others, and makes a case for why they’re worth getting over. And then she offers a few ways forward: get to know black families. Restrict your diet of nightly news – it doesn’t provide a balanced picture of reality! Join an interracial church. Read some of the history.

Condemning bigotry as monstrous is entirely apt. Condemning every person guilty of prejudice as a monster, on the other hand, is both naive and unhelpful. It’s naive because, in fact, as McGhee points out, prejudice is something everyone struggles with in some form. To pretend that embracing difference is as easy as breathing – that humans don’t naturally gravitate towards people like themselves, or find genuine difference uncomfortable or confronting – is to forget that harmony between different groups of people takes real and sustained effort.

It’s unhelpful because “you can’t say that” may shut someone up, but it also shuts down a conversation that ought to be opened up. It shuts people out of conversation instead of engaging with their fears, frustrations, or areas of ignorance.

If we could draft the perfect law to promote racial harmony and prevent both vilification and the freezing of free speech, that would still be the merest beginning to overcoming prejudice. Law is an invaluable safeguard, but far too blunt an instrument for changing hearts or building a shared culture.

Do we want a public culture where we can believe the best of one another, where we can hope to change each others’ minds rather than condemn one another?

For that, humility on the one side must meet grace on the other. We must suspect ourselves of bigotry. We must take pains to articulate what’s healthy and energising about living with difference. We must find ways to put real faces and names to groups many Australians are tempted to dislike or shy away from.

The current ABC series You Can’t Ask That attempts just this. It takes questions we’re usually told are unacceptable and poses them to those who might be expected to take offence at them – fat people, Muslims, wheelchair users, ex-prisoners, people in polyamorous relationships, indigenous Australians, and so on. Instead of silencing such questions, it turns them into occasions for dialogue.

At the end of an episode, viewers may still find the subjects’ customs strange or uncomfortable, or disagree with their beliefs or choices. But nothing else has the transformative potential of an encounter (albeit still at some remove) with real people in place of an undifferentiated mass of “them.” As Heather McGhee says to Gary, “we know in order to be a people that is united across lines of race and class and gender and age, we have to foster relationships, we have to get to know who one another actually is.” Relationship is everything.

Do we want a public culture where we can believe the best of one another, where we can hope to change each others’ minds rather than condemn one another, and (like Gary) have our own minds changed?

Then we need to worry less about how other people – immigrants, racists, Liberals, lefties – are what’s wrong with Australia, and ask more often, in genuine humility: how can I be a better Australian?

Natasha Moore is a Research Fellow with the Centre for Public Christianity. She has a PhD in English from the University of Cambridge, and is the author of Victorian Poetry and Modern Life: The Unpoetical Age.

This article first appeared at ABC Religion & Ethics.