“I think, therefore I am an atheist” is a slogan branded on bumper stickers, buttons, mugs, hats, and t-shirts. Such accessories are for the atheist proud to declare their allegiance to reason that rules out their ability to believe in God.

The line, of course, shrewdly appropriates Rene Descartes’ famous dictum ‘I think, therefore I am’, a statement that locates in the mind and humans’ rational abilities the basis of all trustworthy knowledge and experience. Yet theories of embodiment have showed the insufficiency of Descartes’ claim, which raises the possibility that the atheist’s reliance on reason, to the exclusion of all else, may not be so reasonable after all.

Atheists frequently present themselves as the champions of reason, and Christians as unthinking and babyish because they refuse to listen to their reason that would lead them to the same conclusion as the atheist: that there is no god. And so a criticism often made of the Christian is that she believes in God because it is convenient for her to do so, not because it is reasonable.

Atheists frequently present themselves as the champions of reason, and Christians as unthinking and babyish because they refuse to listen to their reason that would lead them to the same conclusion as the atheist: that there is no god. And so a criticism often made of the Christian is that she believes in God because it is convenient for her to do so, not because it is reasonable.

The atheist’s accusation makes an implicit demand. If faith in God is to be at all credible, it must be the outcome of reason that has availed itself of the best that the scientific method has bequeathed to us: objective and neutral evidence that is measurable, quantifiable, repeatable. Faith in God must never spring from the heart, or be a product of emotions and need.

They have a point. But the atheist’s demand for reason alone to produce faith seems a bit unreasonable, for it denies the emotional and spiritual aspects of our being that are no less crucial parts of us than our minds.

That our emotions and non-rational (which isn’t, I might add, the same as irrational) natures aren’t taken seriously when it comes to providing valid information about the world is unsurprising. It’s a legacy of the Enlightenment, a period during which human’s capacity for reason challenged the divine right of kings and the dominance of the church to control the destiny of humankind. It was during this period, also known as the Age of Reason, that Descartes gave us his infamous catchphrase.

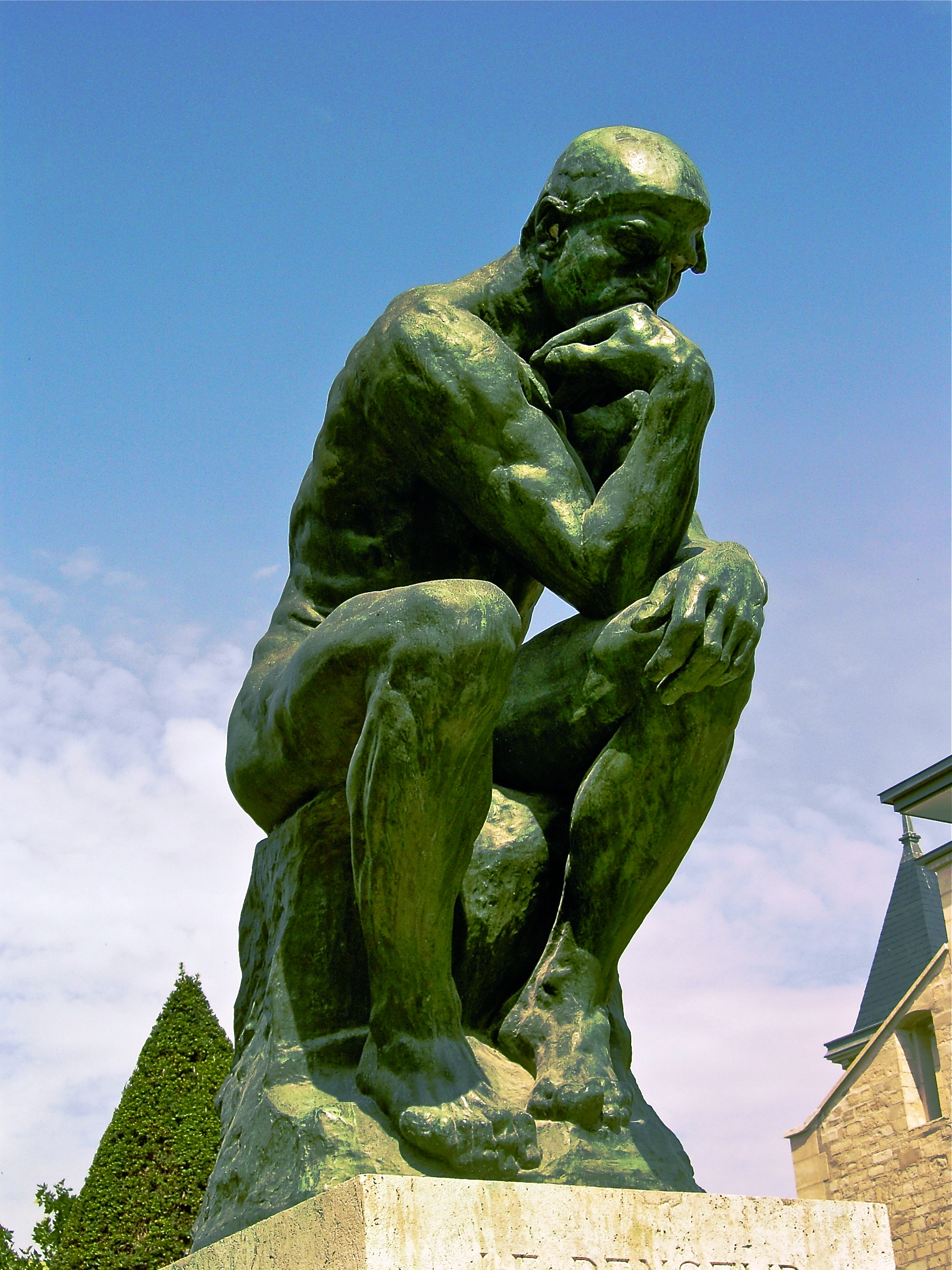

The French philosopher arrived at this conclusion after endeavouring to establish the grounds of all knowledge and enquiry, the basic principles from which would flow every idea and notion ever conceived. He did this by doubting everything he knew, especially the evidence of the world provided to him by his bodily senses because, he reasoned, these could be deceived and so were unreliable.

At the end of all Descartes’ doubting, he realised that the only thing of which he could be sure was that he doubted—that he was a ‘thinking thing’. And so, he concluded, the reasoning mind was the only reliable compass to navigate the mysteries of existence. “I think,” Descartes summarised, “therefore I am.’

Yet cultural theorists have critiqued Descartes’ elevation of reason by analysing how it creates a binary opposition between the mind and body—what they name ‘Cartesian dualism’. The opposed pair of terms (‘mind’ and ‘body’) aren’t equally valued but are stacked in order of importance, with ‘mind’ exalted at the expense of the ‘body’, since Descartes distrusted the sensory evidence that it would supply.

In this binary opposition, ‘mind’ is valued as superior, true and good, whereas ‘body’ and all associated with it is devalued as negative, deceiving, animal, the mere instrument or tool of the mind. Moreover ‘body’, as the debased term of the opposition, is not framed positively and valued in and of itself but is figured negatively, a shadow of its exalted counterpart—body is ‘not-mind’.

This mind/body opposition proliferates in Western culture. It frames our attitudes, values and beliefs by mapping itself onto a variety of other oppositions—for example male/female, White/non-White, West/East, rich/poor, Self/Other, objective/subjective—that work to organise the way we think. The result is that the interests of particular privileged groups (survey the valued terms on the left of each opposition to get the idea) are masked as impartial truth and taken as ‘common sense’: the enemy of critical thinking.

The criticism ‘You’re being emotional’ implies that making a decision rationally is far better than making a decision based on how you feel

Of course, such values work their way into our language. The criticism ‘You’re being emotional’ implies that making a decision rationally is far better than making a decision based on how you feel—which also aims a barb at women since they are so emphatically linked with their emotions. Also, the expression ‘mind over matter’—perhaps used to encourage someone to struggle through their hundredth push-up—emphasises the power of the will to force the compliance of reluctant flesh.

Both of these examples work to segregate the mind from the body, and reason from emotion, suggesting that the further away the mind (reason) can get from the body (emotion), the better. Such an attitude is also glimpsed in the preference for reason above all else that characterises the New Atheism—led by the so-called ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’: Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens. Theirs is an atheism that insists loudly on its truth and reason, but it’s one that does so from a very particular White-Western, privileged, male viewpoint and that tends to sideline other ways of looking at the world.

Our cultural preference for mind over body, and reason over emotion, is probably why atheists will dismiss out of hand Clifford Williams’ thesis in Existential Reasons for Belief in God. In his book, Williams presents the case for what he calls ‘existential apologetics’, which argues that the Christian is justified in believing in God because it satisfies his or her emotional and spiritual needs. So, to the critic who contends that the Christian believes because they need God to be real, the existentially apologetic Christian might respond, ‘so what?’

That may not be much of a comeback, and I doubt existential apologetics will leave its mark in an era that enthrones the scientific method. But Williams’ work reminds us that we’re not simply rational and logical creatures but also human beings with needs, emotions and desires. And so it stands to reason that faith in God should speak to the whole of our beings, not simply our minds. Especially when our emotional life in all its richness, oddity, contradiction and complexity can’t be reduced or explained away on the basis of reason.

It’s a welcome reminder, and one that resonates with theories of embodiment that challenge Descartes’ privileging of mind over body. Such theories don’t simply flip the opposition and make ‘body’ the privileged term. Rather, they deconstruct the opposition of mind and body by demonstrating their interrelation—the fact that each is the necessary precondition of the other.

where Cartesian dualism might lead us to conclude that we have bodies since the body is the mere tool operated by the mind, theories of embodiment might offer instead that we are bodies

Whereas Descartes located identity in the mind, theorists of embodiment argue that we are embodied subjects whose identities emerge from an intricate web of human capacities that includes our intellects no less than it does our sensory abilities. So where Cartesian dualism might lead us to conclude that we have bodies since the body is the mere tool operated by the mind, theories of embodiment might offer instead that we are bodies.

Such theories draw on the work of phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty who argued that perception is something lived and experienced and not simply the result of a distanced mind reflecting on the world, as Descartes might claim. Rather, as cultural theorist Nicole Anderson explains in Cultural Theory in Everyday Practice, “we perceive information through our bodies, which create meaning through sensuous experience.”

Theories of embodiment, then, challenge the notion that the mind and its rational abilities are the basis of all our knowledge. They acknowledge that the body and bodily senses can reveal truths about the world that are not immediately self-evident to a perceiving mind. Take hunger, for example. You don’t think it, but feel it. And while that growling in the belly might be the product of neurons firing in the brain, a signal sent to remind us to eat, hunger is no intellectual fancy but an embodied, gustatory experience.

All of this is not to argue, of course, that theories of embodiment provide a knockdown argument in the face of the atheist demand for reason. They simply give us good reason to question whether reason is the best, or even the only, way through which to know the world. Embodiment reminds us that the body, long the debased counterpart to the preferred mind, may possess an insight of its own.

Such recognition opens up the opportunity for emotions—that like the senses are deeply felt and experienced—to be considered as reasonable grounds for faith. Though emotions can be changeable and unreliable, they can be understood as a kind of testimony offered by the heart and the body, a testimony long ignored and discounted because of our cultural preference for reason over emotion.

In making his case, Williams marshals Pascal’s maxim that ‘the heart has reasons of which reason doesn’t know’, noting that while reason produces arguments for believing in God, “the heart, however, knows God directly, through perception, not through arguments”. And while this ‘soft’ testimony may be inadmissible in a court solely interested in ‘hard’ evidence, the witness offered by the heart gently reminds us that objectivity and neutrality haven’t a monopoly on truth, but that other ways of wisdom exist.

However, Williams doesn’t simply advocate a need-based religious devotion that is utterly devoid of reason. One does not check in their brain upon signing up to belief. Williams proclaims “the ideal way to secure faith is through both need and reason” and explores how to do that in response to several objections that are likely to arise in response to existential apologetics: the fact that need doesn’t guarantee truth or what kind of God is to be believed in, that not everyone feels the same need for God and that many can satisfy their needs without turning to faith.

Throughout Existential Reasons for Belief in God, Williams demonstrates an ongoing, back-and-forth dialogue between reason and need and how they operate in relation to faith. He shows how reason and need challenge and complement each other, and sometimes are not so easily distinguished. But this is not abstract theorising, for he’s included in his book several personal accounts—people’s stories of gaining faith, as well as losing it.

if some Christians believe in God primarily on the basis of need, it stands to reason that atheists choose not to believe in God because they need for him not to be real

These stories speak of people’s need to believe in God, and how their need led them to varied conclusions about their faith. They made me think of those who reject the existence of God and wonder if their reasons and feelings are similarly caught up in a mysterious dance of head and heart that led them to their position of atheism.

In other words, if some Christians believe in God primarily on the basis of need, it stands to reason that atheists choose not to believe in God because they need for him not to be real. People have, in short, just as vested an interest in their atheism as the Christian’s belief in an all-powerful God.

And if we are to be fully embodied creatures and not solely defined by our intellects we need to pay as much attention to our emotional lives as our reasoning minds.

In the end, all of this isn’t about sacrificing fact for what feels good, but about recognising that different approaches offer diverse angles on the truth. I’m reminded of Contact (1997), a film about the search for alien life. When alien beings make contact with the earth, the scientist Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) voyages into outer space to see what kind of creatures they might be.

Upon arrival at a distant solar system so strange, so unnerving, so incredible, Ellie is clearly overwhelmed at what she sees. While she could use the language of science and maths to explain the magnificence of the celestial spectacle Ellie gulps instead, “They should’ve sent a poet.” It’s a small moment in which Ellie recognises the value of a thoroughly non-scientific way of looking at the world to account for the marvel in front of her eyes.

Reason, then, may not give us the full truth of God’s existence (or non-existence) unless it veers towards a reason that is fully embodied: one that is informed by matters of the heart and able to submit its own prejudices to vigorous scrutiny. And perhaps a reason that realises all too well that, to borrow from Peter Hitchens, even the best of arguments stated in prose can’t be compared to cases that are “most effectively couched in poetry.”

Perhaps that kind of reason lights the path to true enlightenment.

Justine Toh is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Media, Music, and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University.

This article originally appeared in Zadok Perspectives No. 114 (Autumn 2012)