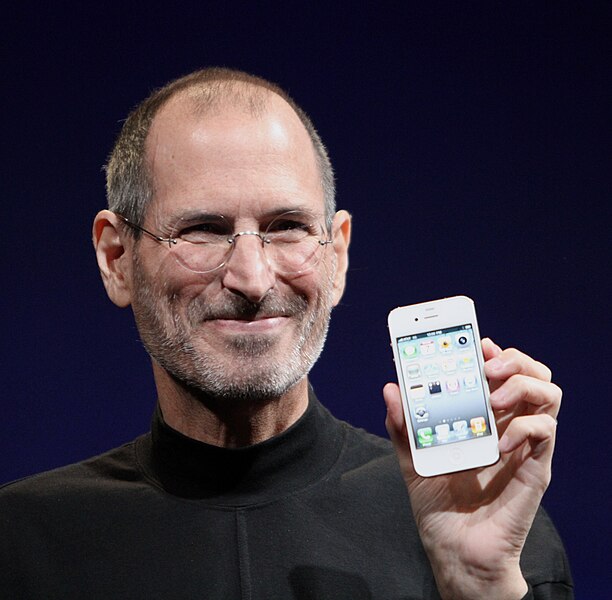

The traditional Christmas story is about the entry of a god into the world. This year, however, we saw one depart. Luckily, his legacy lives on in his relics, so as you unwrap your iPhone 4S this Christmas, you may wish to thank the iGod: Steve Jobs.

Tributes left on Apple’s electronic epitaph to its legendary CEO have all but deified Jobs since his passing away in October. There, messages blur the line between fanboy fervour and religious devotion, like this one left by fan ‘Masayuki’: “Many thanks, Jobs. Your life is My life. For ever.”

The incredible outpouring of tribute to Jobs shows that he wasn’t just the uber cool, turtle-neck wearing CEO who revolutionised the way we relate to computers, as well as each other, with a suite of fabulous gadgets.

Jobs was also an inspirational guru whose incredible achievements gave us reason to trust his stirring rhetoric.

Once, he famously exhorted a crowd of Stanford students to “Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish,” not to be cowed by failure, and not to let others’ opinions drown out their inner voice. Rather, they should follow their intuition and search for work they loved because that would lead to the greatest satisfaction.

Another time, Jobs was blunter: ‘We’re here to dent the universe. Otherwise, why even be here?”

Jobs’ clarion call for everyone to live a big, daring life is irresistible. Few would remain unmoved at such inspiring words. And therein lies the entwined appeal and glory of Jobs the iGod: though few might ever reach his stratospheric levels of success, we can all live successfully by never giving up on our dreams.

All this endows the iPhone, iPad and iPod with a sacramental quality. Though the ‘i’ might originally have stood for ‘internet’, these tools are siren songs from a world where the individual—and their ambitions, hopes and dreams—reigns supreme.

It’s a markedly different world from the one earlier generations inhabited. Just consider Frank Capra’s classic Christmas film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

In that film George Bailey wants to follow his dreams and do “something big and something important,” but circumstances mean he never gets his wish. He grudgingly trades in his ambitions for a decent but unfulfilling job, and continually chooses his family and community’s needs above his own desires—actions that run counter to today’s prevailing wisdom.

In that film George Bailey wants to follow his dreams and do “something big and something important,” but circumstances mean he never gets his wish. He grudgingly trades in his ambitions for a decent but unfulfilling job, and continually chooses his family and community’s needs above his own desires—actions that run counter to today’s prevailing wisdom.

It costs him. George becomes so steadily ground down by the accumulation of many small defeats that he wants to kill himself—a grim note in a film often remembered as sentimental and corny.

Yet his guardian angel intervenes to show George the difference he’s made in his community. By that humble measure, George has lived a ‘wonderful’ life precisely because it’s been lived for the sake of others.

George’s life might repel more than appeal to a ‘Generation Me’ schooled on Jobs-style pep talks.

Psychology professor Jean Twenge, who surveyed the attitudes of her peers born between the 1970s and 1990, writes that she “hated” It’s a Wonderful Life for its affront to all that modern movies had taught her: chiefly, that you must never give up on your dreams.

But George’s life, spent for others’ benefit rather than in pursuit of personal glory, reveals a wisdom that rivals Jobs’ belief in the prerogative of the individual not to settle for anything less than their ambitions.

This wisdom overturns our dominant ideas about success and impact in its radical suggestion that serving others and putting their needs before our own may be more heroic than anything else we might achieve in our lives.

Maybe such an ethos is simply outdated for our self-obsessed times; It’s a Wonderful Life too twee and nostalgic for our cynical century. But it’s a wisdom that resonates with the heart of Christmas.

For that story, too, is also one of reversal: of a God of infinite abilities limiting himself to the vulnerable form of a baby, of glory and might wrapped in swaddling cloths rather than rich, luxurious robes. And of the man that baby would grow up to be, one who always looked to others’ needs before his own, even at the cost of his life.

Greatness, in the terms of that Christmas story, isn’t about public adoration or pursuing one’s dreams but the life of sacrifice, often lived away from the attention of the crowd.

The choice to forgo status and influence for the benefit of others offers a radical challenge to a culture that worships power and clout. Such a vision, while less conspicuous, may do more than merely ‘dent the universe’.

Justine Toh is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Media, Music, and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University.