There’s been more than one occasion in recent years when I’ve wondered whether the word ‘Christian’ is even helpful in describing what I am and what I believe. That’s potentially awkward when you work at the Centre for Public Christianity!

There’s been more than one occasion in recent years when I’ve wondered whether the word ‘Christian’ is even helpful in describing what I am and what I believe. That’s potentially awkward when you work at the Centre for Public Christianity!

Every time some crazed pastor decides that not only is the latest, tragic, natural disaster a direct punishment from God, but the said cleric has the inside word on the particular thing that has incurred the wrath of the almighty; when people claiming to be Christian publically burn Qurans or advocate policies that will crush the poor, or engage in hateful talk about people they disagree with, I want to protest that this is not a reflection of the Christian faith or the Jesus that I follow.

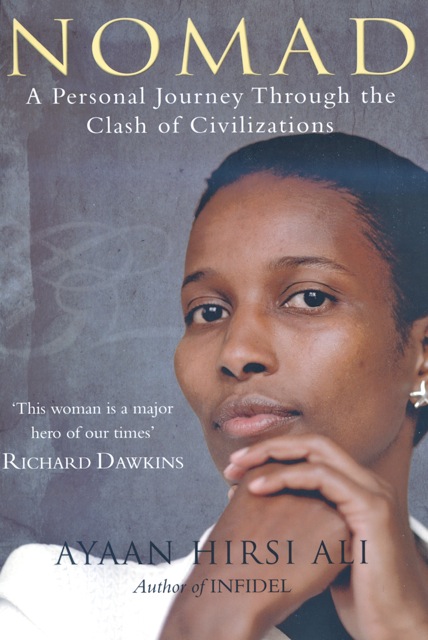

Having read Ayin Hirsi Ali’s latest book Nomad, I am left wondering whether people of Muslim faith might have a similar reaction to her work.

Nomad recounts Hirsi Ali’s experience of, and ultimately escape from, Muslim culture in Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya and Saudi Arabia. She contrasts that life with her experiences in the Netherlands and then the U.S.A where she now lives, aiming to show the superior nature of life in the West and the threat she says that Muslim culture represents to that life. She pulls no punches, squarely attacking what she thinks is a religious system diametrically opposed to the freedoms and lifestyles that Westerners love, take for granted and are in danger of losing.

When she was a member of the Dutch parliament, Hirsi Ali famously made a film with her friend Theo Van Gogh, about the treatment of women in Islam. Van Gogh was murdered as a result, and Hirsi Ali has had to live with protection ever since. In 2007, she wrote Infidel, which secured her status as an advocate for those opposing the spread of radical Islam, and a hero of secularist and humanist groups.

The first sections of Nomad focus on Hirsi Ali’s experiences, and that of her family—cousins, sisters, nephews and nieces—living within Islam. In her eyes, it was (almost) all bad. Her own family is presented as the picture-perfect illustration of Islamic dysfunctionality with life characterised by violence, fear and oppression (especially for women), with some better moments in between.

Her ‘letter to her grandmother’ written from the West at the death of the old women, is a moving account of all that was wrong with her upbringing and why she has rejected the faith of her forbears. “Salvation lies in the ways of the Infidel,” she writes, and gives detailed attention to the things about life in the West that she has come to appreciate—free enquiry and the encouragement to think critically, equality between the sexes and individual choice in education, sexual expression and, importantly, religion.

Hirsi Ali paints a vivid picture of her early life being inherently violent. “I got used to the practice of violence as a perfectly natural part of existence,” she says, and recounts beatings by family members, and even having her skull fractured against her living room wall by her private Quran teacher. She talks about disturbing levels of violence in Muslim immigrant families now residing in the West from countries such as Turkey, Morocco, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan, and Nigeria.

Hirsi Ali says that Muslim families place much value on politeness, friendliness, and charity, but hold conformity to Allah’s will in the highest regard. Violence is thus thought of as a legitimate means of enforcing that conformity, and is an integral part of social discipline. (191)

The nagging question for the reader of Nomad however is just how typical Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s experiences could be said to be. There is no doubt that she was raised within the confines of perhaps the worst of African tribalism and the most conservative branches of Muslim expression. But in what sense does that represent the broader Muslim experience? That is the sticking point of the book that requires further investigation.

“All human beings are created equal,” she declares, “but all cultures and religions are not.” (212) There will be plenty of readers, Muslim or not, who will take issue with her at this point.

Hirsi Ali’s argument centres around what she discerns as a growing clash of civilisations as Islam spreads around the world and Muslim immigrants find their way to the West. The challenge is to integrate successfully, she says, and for Hirsi Ali, three barriers stand in the way. First, Islam’s treatment of women, which she sees as deeply unjust, restrictive and damaging, creating an atmosphere where girls are raised to become “submissive robots”. Second, is what she identifies as the difficulty of many Muslim immigrants in dealing with money—attitudes to credit and debt and lack of education especially for Muslim women in financial matters, being a handbrake to progression and growth. Third, is what she sees as the closing of the Muslim mind, stemming from the uncritical acceptance of the Quran as God’s infallible, unquestionable word.

The remedies, according to Hirsi Ali are available and in urgent need of implementation. First of all, she holds great faith in education so as to spread ‘Enlightenment’ values as a means of challenging Islamic culture. She talks a lot about individual freedom and the assumptions in the West that everyone, regardless of sex, ethnicity, religion, or class can increase knowledge by asking questions and seeking answers. The key for her is the enquiring mind; something she feels is hobbled in Islam but encouraged in the West. She says she learned very quickly to value these things more than the Westerners around her who took them for granted. (212)

She has no time for what she sees as well-meaning but misguided Westerners who think that immigrants must be allowed traditional practices and group cohesion so as to maintain self-esteem and mental health. Accordingly, her ideas on multiculturalism as it is practiced in countries like Australia and Britain, are anything but politically correct.

| “In the real world, equal respect for cultures doesn’t translate into a rich mosaic of colourful and proud peoples interacting peacefully while maintaining a delightful diversity of food and craftwork. It translates into closed pockets of oppression, ignorance and abuse.” (213) |

“All human beings are created equal,” she declares, “but all cultures and religions are not.” (212) There will be plenty of readers, Muslim or not, who will take issue with her at this point.

The second remedy Hirsi Ali identifies to counteract the ills of Islam is Feminism—a force that has in equal measure provided her with both hope and disappointment thus far. The narrative of her life is one of escaping a world of confinement and threats; the notion that, because of her gender, she was intended only to serve and honour others. So it is no surprise that she looks to Feminism for the way forward. She calls on the powerful women of the West to challenge and overthrow the tribal honour-shame culture of Islamic religion. She fears that feminists of the West have neither the courage no the clarity of vision to attract women from Muslim cultures and help free them from what she clearly thinks is crippling bondage.

Thirdly, and perhaps most surprisingly, Hirsi Ali locates deep resources within Christianity to resist the spread of Islam. These days she’s an atheist, but says that Christianity is much preferable to the faith of her childhood. She associates Christianity with the progress of the West, says it is more humane, more accepting of criticism and debate and, vitally, allows adherents to leave the faith.

She believes that most Muslims are appalled at the violence that is perpetrated in the name of their faith; are looking for a redemptive God who can help them to know right and wrong. In her mind that means they are looking for a God like the Christian God, but instead are finding Allah. Too many Muslims don’t know about Christianity, she says, and urges Christian churches to get into the places where Muslim immigrants are living and convert as many Muslims as possible to Christianity, “introducing them to a God who rejects Holy War and who has sent his son to die for all sinners out of love for all mankind”. (247)—the difference according to Hirsi Ali could not be more stark.

Hirsi Ali is extremely popular among the New Atheists, so for Christians accustomed to stinging attacks from the likes of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, it is somewhat amusing and ironic that she urges cooperation between secularists and Christians against a common enemy. In her estimations it’s not faith per se that is the problem, only a particular version of it.

As an outsider it’s a little hard to know what to make of Hirsi Ali’s damning assessment of the faith of her youth. It’s obvious that many thoughtful Muslims will argue that her depiction of Islam is skewed to the point of being unrecognisable, even allowing for the realities of her lived experiences. There are of course many people who could, similarly, describe wretched existences being brought up by families and communities professing Christian belief. In these instances the onus is on Christians to explain which aspects of the belief and practice are and which are not, true to the original teaching and the heart of the faith. Hirsi Ali, while more vocal than most, is not alone in offering a formidable challenge to people of Islamic belief. In the interests of healthy dialogue it is now important that Muslims engage with this kind of critique and honestly and openly provide thorough and honest responses to them.

Simon Smart is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity