“Make chivalry great again.” OK, the slogan needs work. It might even be triggering. Pity, though. After some bruising weeks in federal parliament, perhaps reviving a social code that obliges men to mind themselves around women might improve relations between the sexes.

Yes, even – or especially – in Parliament, where, let’s face it, no party’s looking great right now. For a fortnight, the Liberals were out for blood – grilling Labor’s Katy Gallagher over what she knew about Brittany Higgins’ rape allegation; allegations that Bruce Lehrmann denied and led to charges being dropped after a mistrial.

By Thursday of the first week, the Liberals were facing their own issues. Peter Dutton swiftly booted Senator David Van from the party room, based on three separate allegations of sexual harassment, although Van denies all wrongdoing and the allegations are yet to be formally investigated.

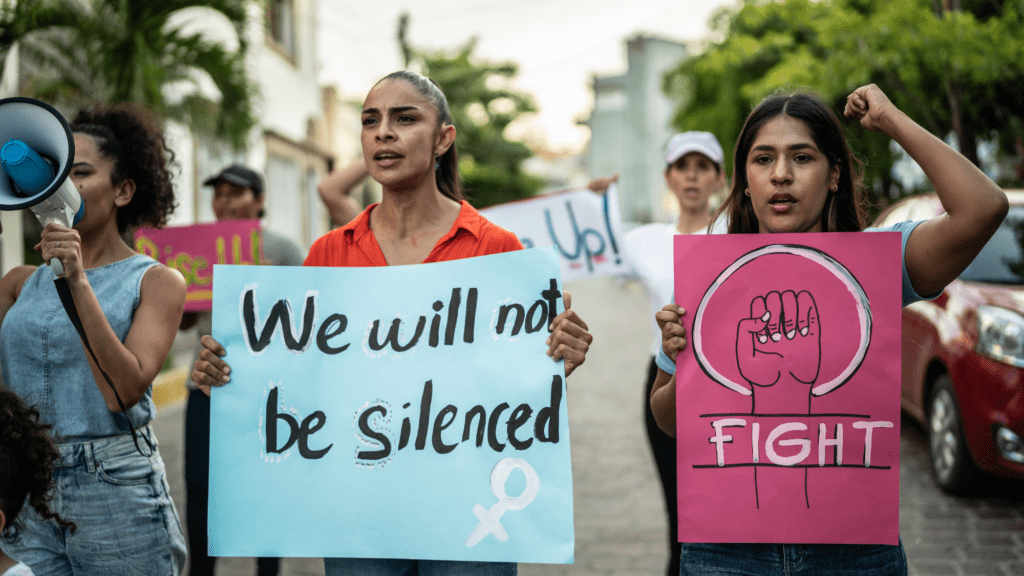

Two years ago, Higgins, Chanel Contos and Grace Tame found themselves spearheading a movement driven by women’s collective rage at sexual misconduct. Two years later, here we are, with a lingering sense of deja vu. What exactly has changed?

On the plus side, consent laws got a much-needed update in 2022. There now needs to be clear communication that “yes means yes”. But if bottoms are allegedly being pinched and women are allegedly getting cornered in dark, parliamentary hallways, then there’s clearly a long runway of behaviour that needs addressing before anyone gets near the bedroom. (And maybe, by the way, consent isn’t enough, as Washington Post columnist Christine Emba has argued.)

Enter chivalry. Admittedly, it seems downright medieval. Can’t argue – it was big around a millennium ago. For liberated moderns, chivalry reinforces rigid and retrograde gender roles: think brave knights and swooning damsels in distress, or excessive, flowery displays of courtly honour that underline female helplessness. That “honour” word raises eyebrows too, especially concerning women, since it links a woman’s value to her virginity and chastity – more terms that clang on the ear in a post-sexual revolution world.

Chivalry just seems outdated, condescending, and “benevolently sexist” because it reinforces the idea that it’s men’s job to protect women – and fawn over them. You can see the latter in the sometimes cringy ways that older men treat younger women, with over-the-top gentility and/or through behaviour that younger generations vibe as inappropriately handsy. It’s super awkward (not to mention borderline sexual harassment) but if you’re anything like Eva Longoria, you learn to deal with it deftly, the way she did with US President Joe Biden last week.

(Mind you, if a woman has to fend off an American president, she’d probably much rather Biden than his predecessor, recently found liable for sexually abusing journalist E. Jean Carroll in a Manhattan department store change room. And yes, neither option is great. We should work towards a world where no woman is faced with them.)

Here’s where a 21st century reboot of chivalry could make a difference. Think of it as a form of gendered realpolitik. #MeToo and its various spinoffs – #ChurchToo, #MeTooSTEM, #MeTooMilitary, #AidToo – have identified a common theme: powerful men are more likely to be the perpetrators of sexual harassment. Sure, #notallmen. But there’s a pattern here.

A renewed sense of chivalry could rest on the pragmatic recognition that, in a world where men enjoy disproportionate power and influence, they are, on balance, more likely to be handsy, more likely to manspread, more likely to mansplain and, therefore, more likely to need reminding that they share a world with multiple others – not just women – who don’t share the same perks. So, gents: behave yourselves.

Chivalry is a reminder to check your privilege: that all things being unequal, other people are always owed your personal respect.

Look, we can all agree that we shouldn’t need a crude social code that explicitly reminds men not to mistreat women. Still, the hotline of a prominent campaign against family and domestic violence literally spells out 1800RESPECT – even if, you know, respect between the sexes should be patently obvious. Sometimes we need things broken down for us.

Neither would a new chivalric order simply make peace with the world’s present injustices. It could potentially sensitise the powerful to inequality of all kinds. That’s because in spirit, chivalry is a reminder to check your privilege: that all things being unequal, other people are always owed your personal respect. And that an attitude of humility – promoting the welfare of others before your own – is an excellent foundation for good social relations. Pay that forward enough, at scale, and who knows what revolution – not just in morals – might result?

Seen from that perspective, chivalry may present as a darling of the political right but its guiding philosophy, weirdly, skews left – because it has the vulnerable in view.

So, it’s a shame that, as far as brands go, “chivalry” is dead. Despite its problems, we should mourn its passing. If male-female relationships are going to improve then it – or something like it – needs to be revived.

Justine Toh is senior fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity.

This article first appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald.