Academic tomes on Jesus often begin their account of previous scholarship with the great German scholars Hermann Reimarus and David Strauss and their attempts to apply the critical insights of the Enlightenment to the study of this central figure of Western history.

These writers stand in a long line of scholars known for their scepticism regarding traditional teachings about Jesus and their quest to separate historical fact from religious understanding of who Jesus was and what he did. But it would be wrong to think that historical questions about Jesus began to be raised only two centuries ago, as if our own Modern era, or Post-modern era, was the first to think critically about this topic. It is a conceit of every age to suppose that it has discovered the most important questions—and answers.

The quest for the historical Jesus really began as soon as he left the scene in AD 30.

The quest for the historical Jesus really began as soon as he left the scene in AD 30.

The Ancient Quest

Even the author of one of the four New Testament Gospels shows an interest in searching out the facts rather than opinions about the man from Nazareth. The Gospel of Luke opens with these telling words:

Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. With this in mind, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught (Luke 1:1-4).

Whatever else this is, it is the statement of someone committed to weighing earlier sources, gathering (eyewitness) testimony, researching thoroughly and then providing an orderly account of the most reliable data. Indeed, Prof. Richard Bauckham of Scotland’s famous University of St Andrew’s—famous for more than being Prince William’s alma mater—has recently shown that Luke’s declared interest in ‘those who from the first were eyewitnesses’ is strongly reminiscent of other historical writers in ancient times, including Polybius, Dionysis of Halicarnassus and the first century Jewish writer Josephus.

Bauckham identifies a host of ‘historiographic’ features in the Gospels, which underline for the modern historian just how keen these biblical writers were to preserve trustworthy testimony about Jesus, and eyewitness testimony in particular. The idea that the Gospel writers were interested in ‘spiritual truths’ rather historical events is as false as it is out-of-date.

By the second century, the New Testament Gospels were widely read and revered by Christians all over the Roman Empire and beyond. Wherever there were Christians in this period there were Gospels, and wherever there were Gospels there were people becoming Christians. Despite this reverence shown to the Gospels, we must not think that Christians all approached their sacred books with pre-scientific blind faith. Intellectuals like the famous Origen of Caesarea (AD 185-253) were as meticulous in analysing the Gospels as anything we observe in modern scholarship. His approach is worth detailing.

Origen lived in a period of intense criticism of Christianity. While still a teenager his father was martyred for the Faith, an event that would have a huge impact on this young virtuoso. He threw himself into his studies, not only of classical subjects like Greek grammar, mathematics, rhetoric, history and philosophy but also of Christian theology. And when he turned to the Gospels themselves, as he did time and time again during his fifty-year academic career, he was relentless in his analysis.

Origen made judgments about the details of the Gospels that would make contemporary fundamentalists a little queasy, but he remained a firm believer to the end

Origen consulted as many manuscripts as he could find for each of the Gospels. He wanted to reconstruct the most accurate form of the text: today we call this Textual Criticism. He assessed the geography of the Gospels against his own personal knowledge of Palestine, something archaeologists are still doing. And perhaps most impressively, he carefully compared the four Gospels with each another, honestly noting the differences between them. He did not try to harmonize the accounts into one neat version of the Jesus story, as others had done.

Instead, he wanted to discern each Gospel writer’s particular emphasis and editorial hand. Scholars today call this Redaction Criticism. Sometimes Origen made judgments about the details of the Gospels that would make contemporary fundamentalists a little queasy, but he remained a firm believer to the end, absolutely committed to reading the whole Bible as the Word of God. (His scholarship on the Old Testament was equally dazzling). It was precisely Origen’s faith in the God of Truth that fuelled his commitment to search for the truth about Jesus.

We could devote many more pages to exploring the work of scholars in ancient and Medieval times who applied their significant intellectual powers to the analysis of the Gospels and Jesus. Among the stars of the story would be Eusebius of Caesarea (260-339), Saint Jerome (331–420), John Chrysostom (347-407) and Saint Augustine (354–430); and at the dawn of the modern period, Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) and Martin Luther (1483-1546).

With due respect to the towering figures of Medieval scholarship, I want to race forward to one of the most significant periods in human history—a period that would change forever how we study Jesus.

The First Quest: the confidence of the Enlightenment

The so-called ‘Enlightenment’ was a European intellectual movement of the 17th-18th centuries which emphasized the power of human reason to discover all that was valuable in life. Buoyed by the significant literary and artistic successes of the recent Renaissance period (1400s-1500s) Enlightenment thinkers felt free to question everything. They would not be constrained by mere tradition, whether cultural or ecclesiastical, and the consequences for biblical studies were significant.

Whereas earlier scholarship was inspired by its faith in Christian teachings, Enlightenment scholarship was guided by its confidence in human reason. I should point out that neither approach really lacked the application of reason, as the example of Origen amply demonstrates for the ancient period. Equally, it has to be said that neither really lacked a faith-commitment either. As the philosophers remind us, the prerequisite of all intellectual enquiry is trust in the efficacy of one’s rational powers.

Enlightenment scholarship was absolutely confident in its ability to separate fact from fiction in the Bible. It could do this using linguistics, historiography, archaeology and philosophy, without recourse to the ‘dogmas’ of the Christian church. Many have called this movement the ‘First Quest’ for the historical Jesus.

The ‘revolutionary Jesus’ of Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768)

German scholar Hermann Reimarus epitomized the Enlightenment spirit and in some ways can be said to have launched the First Quest.

Reimarus was a professor of oriental languages in Hamburg and a thoroughgoing ‘Deist’; he rejected the idea that the Creator had revealed himself to humanity (either through the Bible or elsewhere). It was out of this academic and philosophical perspective that he wrote his stinging critique of orthodox Christianity titled Apologia or Defence of the Rational Worshippers of God. He originally made it available only to a close circle of friends but, after his death, sections of the work were published by the philosopher G. E. Lessing. These included chapters titled On the Resurrection Narratives and On the Intentions of Jesus and His Disciples.

Reimarus proposed three new ideas. First, he insisted that we distinguish between what Jesus actually said and did and what the apostles merely claimed he said and did. In other words, he posited a significant difference—even contradiction—between the ‘Jesus of history’ and the ‘Christ of faith’. Many echo this sentiment today without realising where it came from.

Secondly—and perhaps a little surprisingly to modern ears—Reimarus maintained that Jesus was a failed political revolutionary. His reasoning was in three parts: (1) many ancient Jews thought of God’s coming kingdom as an earthly reality destined to overthrow the Romans (that’s true); (2) Jesus, who was a Jew, also talked a lot about the ‘kingdom of God’ (that’s true too); and (3) Jesus must therefore also have intended to oust the Romans and establish a political kingdom. Jesus was executed, then, as a dissident. Any teachings or deeds of Jesus in the Gospels that moved in a different direction—e.g., ‘love your enemies’—was likely, said Reimarus, to be the result of the apostles putting words into Jesus’ mouth sometime after his political agenda had failed.

the third idea in Reimarus’ rational reconstruction of the historical Jesus. The saviour figure described in the Gospels and proclaimed by the church ever since is a deliberate deception crafted by the apostles

This introduces the third idea in Reimarus’ rational reconstruction of the historical Jesus. The saviour figure described in the Gospels and proclaimed by the church ever since is a deliberate deception crafted by the apostles. Unable to let go of their commitment to the failed Jesus, the first disciples stole the body of Jesus from the tomb, invented a story about his being raised to life and then proclaimed him to the world as a divine redeemer (rather than a political revolutionary) who would soon appear to end the world. The fact that such a redeemer did not reappear, said Reimarus, means that the entire Christian religion is irrelevant.

The ‘mythical Jesus’ of David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874)

Reimarus’ extreme scepticism and anti-Christian agenda were cemented (and slightly moderated) by another Enlightenment scholar, and another German, David Strauss.

In one of the most influential books of the 19th century, Strauss’ The Life of Jesus Critically Examined (published in 1835-36) argued that the Gospels need to be understood as Myth. ‘Myth’ does not mean simply untrue; nor did Strauss go along with the idea that the apostles set out to deliberately deceive. What he meant was that wherever the Gospel writers strain our rational minds—as in the miracle stories—they are employing the religious imagination to express the inexpressible longings of the human soul. The resurrection narratives, for instance, are not out-and-out lies; nor are they historical reports. They are rather poetical images (myths) of the divine life which the early Christians longed for.

Unlike Reimarus, David Strauss believed that the core ideas of Christianity—peace and love and all that—could be preserved even if the main events are unhistorical. Someone like Bishop John Shelby Spong is a modern example of a theologian in the Straussian model.

The ‘wise man Jesus’ of Joseph Ernest Renan (1823-1892)

David Strauss launched a flurry of very confident critical analyses of the life of Jesus. In 1863 the French philosopher and historian Ernest Renan published his Life of Jesus in which he cast Jesus as a charming and wise Galilean preacher whose initial popularity soon waned—to the point of outright rejection—on account of the high demands he placed on his followers.

The First Quest was beginning to take its shape. Jesus as the simple, wise teacher would become a stock theme in many discussions about him (even today).

The ‘failed Jesus’ of Heinrich Julius Holtzmann (1832-1910)

In the same year (1863) another important book was published in Germany by Heinrich Holtzmann. The Synoptic Gospels argued that Mark was the first and most reliable Gospel. Matthew and Luke had used Mark’s Gospel and then supplemented their works with material from another early source known as Q (from the German Quelle, ‘source’). This theory has stood the test of time.

Other aspects of Holtzmann’s work have not fared so well. For instance, he argued that Jesus’ life and ministry developed in two distinct stages: an early successful period, when he was a simple preacher of timeless moral principles; and a later period of failure, when he began to think of himself as a Messiah destined for suffering. The outline was neater than it was credible.

The ‘non-Messiah Jesus’ William Wrede (1859-1906)

Holtzmann left intact at least some confidence in two basic historical ‘facts’: firstly, that Mark’s Gospel (if none of the others) was a broadly accurate account of Jesus’ life and, secondly, that Jesus himself had claimed to be the Messiah. Both of these propositions were dealt a major blow in 1901 with the publication of The Messianic Secret by William Wrede of the University of Breslau (Polish Wroclaw).

Wrede surmised that Jesus himself never suggested he was the Messiah (he was simply a great teacher).

Wrede drew attention to the fact that in Mark’s Gospel Jesus occasionally asks people not to tell anyone that he is the Messiah. He further noted that the New Testament frequently pins Jesus’ messianic credentials not on his earthly ministry but on his supposed resurrection from the dead. From this Wrede surmised that Jesus himself never suggested he was the Messiah (he was simply a great teacher).

The messianic idea was invented by the disciples after Jesus’ death and then written back into the story retrospectively. Because Jesus’ contemporaries knew he never made claims to messiahship, Mark had to invent a supplementary idea, said Wrede, designed to explain Jesus’ apparent silence on the matter: Jesus revealed his identity only to his closest disciples asking them to keep it a secret until after his death and resurrection. In this way the early Christians turned a noble preacher into the glorious Messiah.

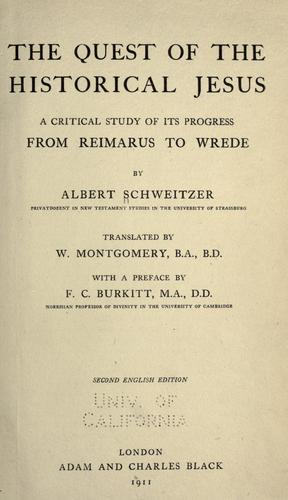

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) and the end of the Enlightenment quest

The strident scepticism of Enlightenment scholars from Reimarus to Wrede must have seemed unstoppable. Perhaps the power of human reason had triumphed over the fancies of Christian faith. No doubt many felt this way. But the confidence was ill-placed. Within a decade of William Wrede’s 1901 publication—within two centuries of the start of the Enlightenment project—the rationalist quest for Jesus would collapse before the work of a man who, as one modern scholar puts it, “stands at the head of the [20th] century like a colossus.”

Albert Schweitzer was a supremely gifted philosopher, historian and theologian, as well as being an accomplished musician. After publishing some of the most significant books on the New Testament ever written (and one for good measure on the music of J. S. Bach), he left academia, completed a medical degree and devoted himself to medical missionary work in Gabon, West Africa. This ‘jungle surgeon’ won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 and, true to form, gave the prize money to a leper hospital.

Albert Schweitzer was a supremely gifted philosopher, historian and theologian, as well as being an accomplished musician. After publishing some of the most significant books on the New Testament ever written (and one for good measure on the music of J. S. Bach), he left academia, completed a medical degree and devoted himself to medical missionary work in Gabon, West Africa. This ‘jungle surgeon’ won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 and, true to form, gave the prize money to a leper hospital.

Winding back the clock, in 1906 Schweitzer published The Quest of the Historical Jesus. It was a stunning critique of the previous 150 years of research from Reimarus to Wrede. In short, he ably demonstrated that the portraits of Jesus offered by these supposedly objective historians were basically ‘projections’ of what they believed to be the ethical ideal. The characterization of Jesus as a simple, noble teacher, for instance, does not arise from the evidence, he argued, but is a construct born of the humanism of the Enlightenment. Such a Jesus is a figment of the scholarly imagination or, as Schweitzer himself put it, ‘a figure designed by rationalism, endowed with life by liberalism, and clothed by modern theology in an historical gab.’ Ouch! It was a simple observation but, once made, it became impossible to read Reimarus, Strauss, Wrede and the others without seeing wishful thinking on every page.

Schweitzer did not go on to provide a full-scale alternative account of Jesus. He simply offered what he called ‘a sketch’. Schweitzer’s Jesus was not a charming teacher of timeless wisdom; he was an ‘apocalyptic Jewish prophet’ (and claimed Messiah) who proclaimed the end of the world and believed he was destined to suffer for his people to save them from the coming apocalypse.

Schweitzer’s analysis was historically compelling; certainly, no one could accuse him of projecting his own ideals onto Jesus. For decades after him scholars in fact wondered whether the Jesus he had described could be of any relevance to the modern world. As Schweitzer himself noted, he had made Jesus ‘a stranger and an enigma.’

Almost single-handedly, then, Schweitzer destroyed the quest for the historical Jesus. Not only had he ‘erected its memorial,’ wrote a scholar of the next generation, he had ‘delivered its funeral oration.’ After Schweitzer historical scholarship on Jesus would remain quiet for a while. Within a few decades, however, historians picked themselves up from the floor, dusted themselves off and began again to search for reliable historical data about the elusive man from Nazareth.

Dr. John Dickson is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University (Australia)