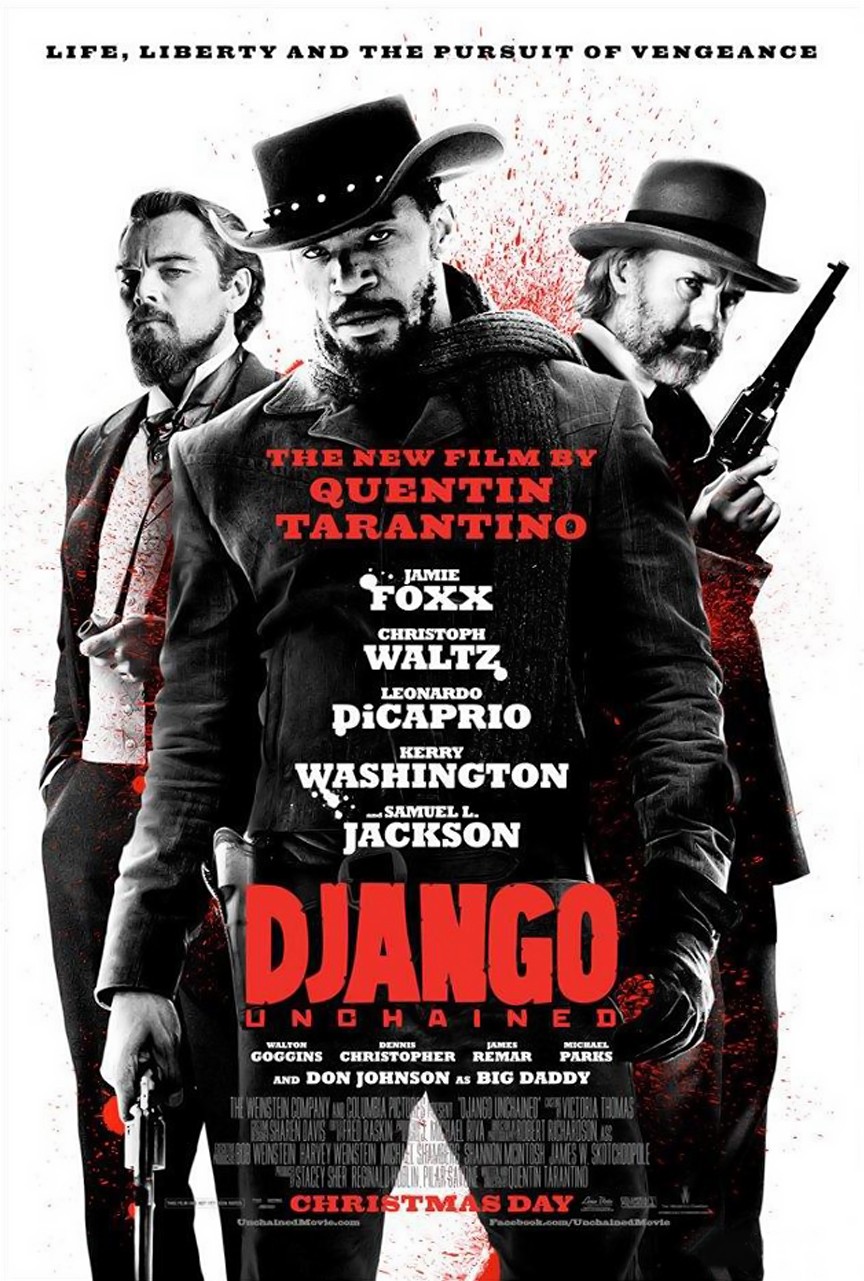

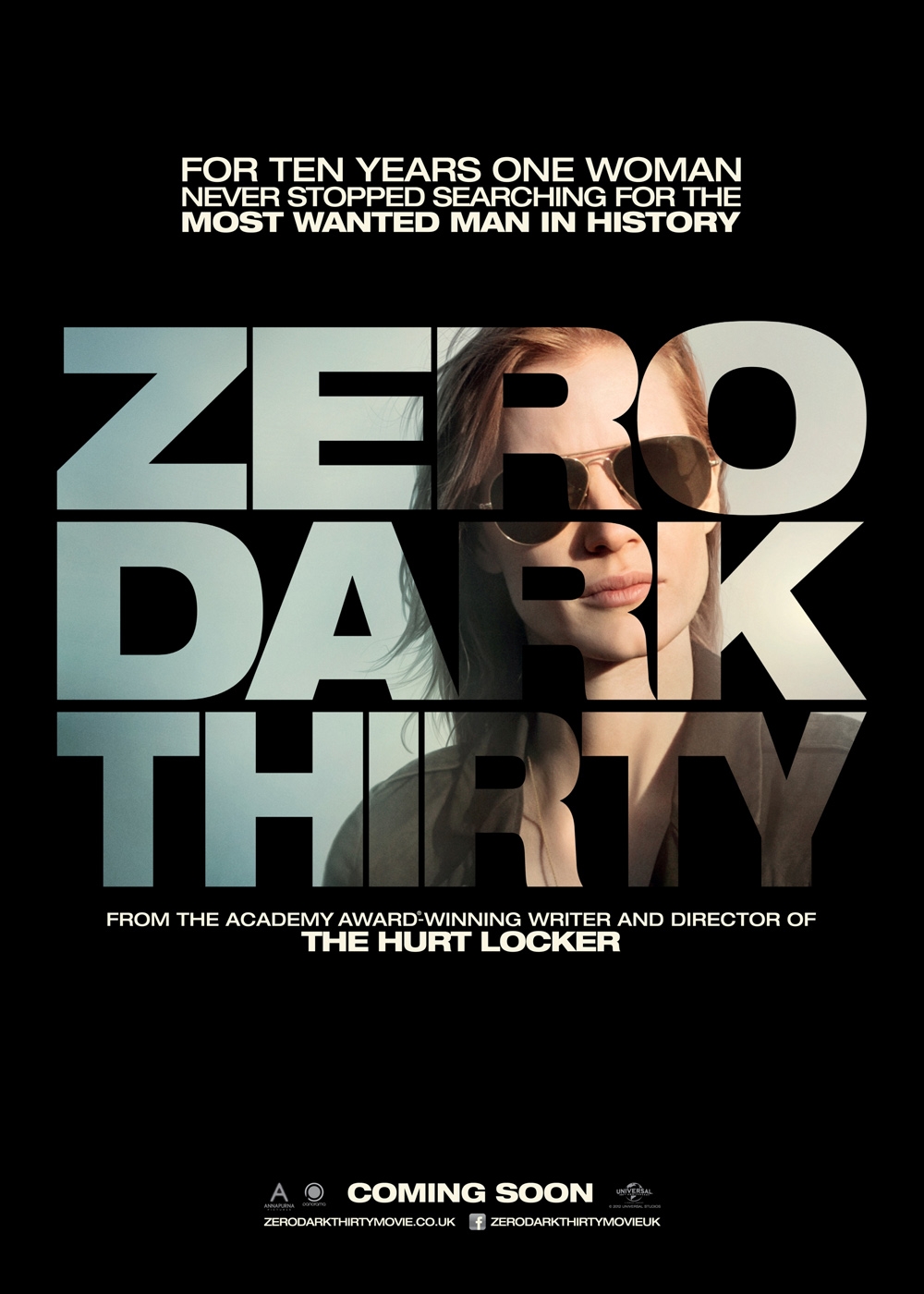

Two recent films – Zero Dark Thirty and Django Unchained – have plenty to teach us about the pointlessness of seeking revenge, writes Justine Toh.

Seeing Zero Dark Thirty and Django Unchained within days of each other was not as wild a swing from the serious to the ridiculous as you might expect.

At first glance the two films couldn’t seem more different, with one seeking to accurately depict the CIA’s decade-long hunt for Osama bin Laden while the other rather-too-cheerily romps its way through the horror of American slavery. But both are united by the bleak belief that vengeance offers the only recourse in a mad, violent world, even if it turns people into the shadow of the enemies they despise.

At first glance the two films couldn’t seem more different, with one seeking to accurately depict the CIA’s decade-long hunt for Osama bin Laden while the other rather-too-cheerily romps its way through the horror of American slavery. But both are united by the bleak belief that vengeance offers the only recourse in a mad, violent world, even if it turns people into the shadow of the enemies they despise.

As with much of director Quentin Tarantino’s recent work (Kill Bill Vol. I & II, Inglourious Basterds), Django Unchained is unapologetic about telling a tale of bloody payback.

From the film’s opening scenes whippings, beatings and brandings all underline the intolerable cruelty of life for slaves under white rule. The brutality and injustice of slavery imbues Django, the hero, with plenty of moral authority that is only enhanced by his desire to rescue his wife Broomhilda from servitude to menacing slave owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio) once bounty hunter King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) secures Django’s freedom.

But, and this is often a problem for Tarantino’s vengeful heroes, the extreme nature of Django’s violent retribution carried out on all at the ‘Candieland’ estate proves an atrocity in its own right.

Django’s legitimate thirst for justice, in other words, is hijacked by his own bloodthirstiness.

A similar issue afflicts Zero Dark Thirty.

Its opening scenes establish the most compelling reason to hunt down bin Laden: the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Though we aren’t shown any images, the audio of anguished voices of victims playing over the soundtrack is sufficiently grisly to evoke that day. But the film then cuts to a black site in Pakistan where Ammar, a detainee with suspected ties to Al Qaeda, is being tortured by Dan, a CIA agent.

Even if bringing bin Laden to justice is the overriding goal of such an interrogation, the use of torture in the film sees American moral authority disappear down a hole as deep as the one in which the terrorist mastermind was presumed to be hiding.

We see this particularly in the rookie CIA agent Maya (Jessica Chastain) who initially flinches at the cruelty of “enhanced interrogation” but hardens up sufficiently to threaten to send an uncooperative detainee to Israel. His treatment there, she implies, will be infinitely worse. It seems that high-minded notions on which the West stakes its reputation – justice, rights, freedom and tolerance – are nice enough but they have no place in the grubby business of tracking down terrorists.

Like Django Unchained, then, Zero Dark Thirty offers us the spectacle of morally compromised heroes whose pursuit of justice and revenge sees them quickly abandon the high moral ground. This muddying of the usually clear distinction between goodies and baddies means that neither film can really claim to have a ‘happy’ ending where good triumphs over evil.

Like Django Unchained, then, Zero Dark Thirty offers us the spectacle of morally compromised heroes whose pursuit of justice and revenge sees them quickly abandon the high moral ground. This muddying of the usually clear distinction between goodies and baddies means that neither film can really claim to have a ‘happy’ ending where good triumphs over evil.

We’ve seen how easily any righteously avenging angel can turn into the enemy they set out to destroy (Django) and can betray their own ideals (the US).

In fact, perhaps neither film can actually claim to have an ending at all.

For while both Zero Dark Thirty and Django Unchained finish, no story that runs off the logic of payback can ever draw to a close – not as long as each side seeks the kind of justice that’s ‘eye for an eye’.

It would be impossibly naïve to pretend that the War on Terror concludes with bin Laden’s death, or that a liberated slave with the blood of rich white people on his hands would ‘live happily ever after’ in the Deep South’s antebellum era. These are merely the latest episodes in a long-running saga with no end in sight.

There’s no recognition of that fact in either film, though to be fair neither sets out to explore the ethics of vengeance. Tarantino, for one, seems more interested in the look of revenge than any moral dilemmas it throws up. But the silence of Zero Dark Thirty on this point feels inadequate.

Perhaps director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal defer a clear statement of their own views because they want the film’s audience to wrestle with hard questions about the US response to 9/11.

The problem is that the overall ambiguity of their film leaves it open to wildly differing interpretations – as the debate over whether Zero Dark Thirty endorses torture makes clear.

Still, it’s not out of the ordinary for a film to muse on the way acts of revenge can trap us in an endless cycle of violence.

Steven Spielberg’s Munich follows the efforts of an Israeli hit squad to eliminate leaders of the Black September Group that orchestrated the murders of Jewish athletes at the 1972 Olympics.

In the film’s memorable last scene, team leader Avner (Eric Bana) despairs that the operation achieved nothing since the terrorist leadership was simply replaced. “There’s no peace at the end of this,” he says darkly, before Munich ends on a shot of the Lower Manhattan skyline featuring the twin towers of the World Trade Centre – it is, after all, the 1970s when they were newly built.

Watching after 9/11, and in the wake of the War on Terror and bin Laden’s execution, the shot is a grim reminder that the prospects of ending violence with further violence are gloomy indeed.

No easy answers exist as to how we might break the links of this infinite chain. But surely a place to start is an attitude that acknowledges the ways in which we – from individuals and groups to governments and nations – have contributed, sometimes unintentionally, to the suffering of others. If we have an ability to examine our own consciences and regret our own failings and weaknesses then perhaps we will be less likely to retaliate when we ourselves are harmed.

It may even be possible to absorb the violence of others – not only by refusing to trade blows with them but by offering forgiveness instead.

Django may succeed in his quest for vengeance but in another sense he makes a grave mistake, for his pitilessness recreates him in the image of his enemy.

But if ‘to err is human; to forgive, divine’ as Alexander Pope has said, then maybe a way out of our sorry history of violence lies in forgiveness and costly moves towards reconciliation.

Justine Toh is the Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity.