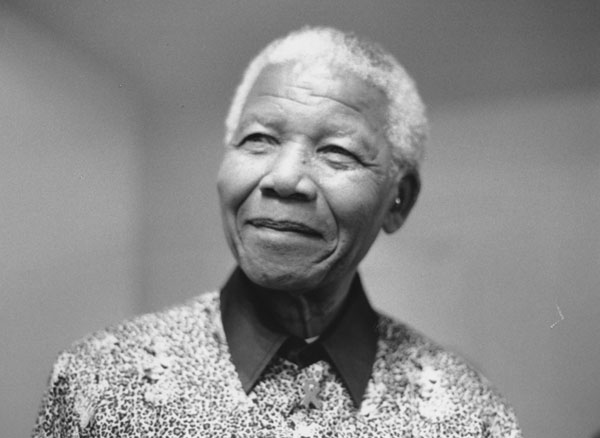

When apartheid ended in South Africa in the early 1990s, many anxiously awaited the sort of bloodbath not unknown with regime change. Instead, the new ANC government under Nelson Mandela introduced the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in which victims and perpetrators, black and white, told their stories.

It was not perfect. More than 20 years later, South Africa is still working through its violent and divided past. More than 7000 perpetrators sought amnesty and under 1000 received it, but few of those who didn’t were prosecuted.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has been called the gold standard for how a divided society might move forward, but without South Africa’s strong undergirding Christianity it would hardly have been possible.

A 2013 Georgetown University study, South Africa: The Religious Foundations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, notes that about 95 per cent of South Africans are affiliated with a Christian denomination, and a high percentage of the population are actively involved in their local church.

“This provides a common set of cultural and theological frames of reference for the country, including Christian understandings of the Golden Rule, forgiveness, mercy, restitution and healing,” the study says. “Christian themes of reconciliation were critical to the commission’s ability to promote national healing.”

It was religious calls for forgiveness that allowed South Africans to go beyond anger.

In all societies, it often seems that genuine reconciliation – which includes repentance, restitution and forgiveness – is humanity’s deepest need.

According to Christian author and commentator John Dickson, reconciliation is the fundamental idea of the whole Bible, the core of the Christian message.

“It’s the notion of the beloved creature that has moved away from the Creator coming back into fellowship and friendship,” says Dickson, co-founder of the Sydney-based Centre for Public Christianity.

“Really, the story from Genesis to Revelation [the first book of the Old Testament to the last of the New] is reconciliation. There is a breach, and the breach needs to be healed, and God has done all that is required to achieve reconciliation.”

Though there are considerable differences between Australia and South Africa, there is a sense that Australians are increasingly divided along lines of tribal identity, whether political, religious, ethnic or gender-based. Attitudes to politics range from frustration to despair, so much so that the Australian National University’s 2018 Australian Values Study found that a third of Australians – more among those under 35 – would prefer an authoritarian leader to elections and Parliament.

Relations between political parties and within them seem more brutal and uncivil than for generations, and 2018 is replete with examples, from the removal of a prime minister by his own party to MPs quitting their parties to avoid unpleasant behaviour. Julia Banks, who left the Liberal Party citing bullying, did not respond to requests for an interview, and in fact no politician, current or former, approached by The Sunday Age for this article would talk.

Many commentators, such as sociologist Hugh Mackay, believe reconciliation is profoundly needed in Australia. “It’s enormously important, and in the non-religious context it means finding ways of resolving our differences by respecting each other and engaging in a spirt of community.”

To be human is to be part of a social species and when members of that species become disconnected from each other, we pay a very high price.

The challenge facing Australia and most Western societies is that we are becoming more individualist, competitive and socially fragmented, he says. This is driven by many factors, ranging from shrinking households, the rate of relationship breakdown, busyness and mobility to engagement with IT devices at the expense of personal connections.

“To be human is to be part of a social species and when members of that species become disconnected from each other, disengaged, fragmented, we pay a very high price, which is an epidemic of mental illness, especially anxiety and depression. These are the symptoms of an unreconciled society,” Mackay says.

Louise Newman, professor of psychiatry at Melbourne University and director of the Centre for Women’s Health at the Royal Women’s Hospital, has worked extensively with victims of torture. She says reconciliation is not as simple as forgetting and forgiving, because that’s often not possible.

A moral and existential perspective is a hugely important capacity, especially in dealing with negative experiences – “not just to understand in an intellectual sense, but to turn it into something creative”, she says.

“There’s a process or moral struggle to come to terms with the human capacity for evil. The various holocausts are examples – your friend can become the person trying to kill you the next day.”

Freud discusses the veneer of civilisation, and the churches have a long history of trying to minimise humanity’s baser instincts, but these issues are always there, Newman says.

“People have to live with the unknowable and incomprehensible, and that can be very much a religious enterprise. The trendy word at the moment is acceptance, but the worst thing that can happen is that people come to a vague acceptance but don’t deal with it properly and are tormented their whole lives.

“Primo Levi [the Jewish-Italian survivor of Auschwitz and author of If This Is a Man, who killed himself decades later] came to an understanding of terrible things, but could not live with it. Sometimes reconciliation with perpetrators is possible, but not just because people say it’s good to reconcile and forgive. It’s about saving the self.”

Newman fears that Australian politics has lost its moral compass in favour of a total preoccupation with political power for its own sake. “I’ve never seen it as starkly as this and it’s very, very troubling to young people.”

Monash University political scientist Paul Strangio is not so sure. A long-term view shows more bitterly polarised times, such as the conscription debates a century ago in which elements of ethnicity, class and religion combined for highly volatile and damaging results, or the Cold War or Vietnam War debates.

What is different today, he says, is the lack of civility and the significant trust deficit not only in government but in religious and corporate institutions. We are also dividing along less predictable lines of social identity, which makes the divisions more complex and less predictable. There are a lot of side winds.

Nevertheless, he says, Australia is much better off than the United States or Europe. Political parties, around which our system is based, are struggling to cope with the more fragmented system, but nevertheless the centre is holding.

“Will we come out the other side? I’m an optimist. We may need to think about our representative democratic system, whether it’s a horse-and-cart model for the 21st century. But this phase is not necessarily the future,” Strangio says.

“The world often seems like it is going to hell in a handbasket, but when you are in the middle of it, it can be very difficult to see beyond that,” he says. A decisive result at the next federal election might usher in a new period of stability.

La Trobe University emeritus professor of politics Judith Brett, author of an acclaimed biography of Alfred Deakin, Australia’s second prime minister, notes that Australia’s adversarial political system leads to a reluctance to compromise for fear of seeming weak.

The solution: minority government. Deakin, in that position, compromised and put the national interest above party considerations. Brett says Deakin believed his reliance on the opposition or independents was a good thing, strengthening his achievements, for it made his government’s legislation not just the achievement of one party but “organic Australian policy”.

Right now there’s a profound public irritation at modern Australian politics. But there is despair at the failure to take climate change seriously, she says, “and the feeling that everyone burns. There’s an undertone of existential despair, we can’t escape the fate of our species, and the species is flawed.”

The Christian model of reconciliation is the most far-reaching because it starts in our deepest psyche with alienation from God and each other.

And that brings us back to the Christian understanding of reconciliation, as a gift of God to those unable to help themselves.

The Christian model of reconciliation is the most far-reaching because it starts in our deepest psyche with alienation from God and each other. Once Christians spoke of sin, but that word has been lost to purveyors of slinky negligees and luxurious chocolates, so English author Francis Spufford has coined another phrase that religious and non-religious alike can recognise of themselves: “The human propensity to f— things up.”

John Dickson points out that the word “sin” simply means to fall short, and we all acknowledge that we have failed to attain our own virtues (let alone the Almighty’s). All of us, if we are honest, know we have fallen short.

World Vision chief advocate Tim Costello turns to the same concept, made explicit by St Paul in his letter to the Romans, that “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God”.

Costello says: “Right at the heart of human frailty is that someone feels superior to someone else who feels humiliated. A lot of conflict comes out of humiliation.”

The recognition that all have sinned is fundamental at the psychological level as well as the spiritual and political – there is no basis for superiority or inferiority.

“That Jesus humbled himself and absorbed the worst humiliation imaginable shows that even God lays down his superiority and invites you to lay down yours, and that is the starting point for reconciliation.”

Costello says the desire to feel superior seems hard-wired. But Jesus admonishes the rich young ruler who calls him “good teacher”, replying “no one is good except God alone”. A common problem in World Vision’s work in tribal cultures, Costello says, is when a tribe’s sense of superiority and entitlement is too strong, “and that sense of entitlement is spreading across the world”.

So are we trapped in a cycle of division and bitterness, or is there a way forward? Hugh Mackay is confident there is, but it must start at the local level. The pathway to reconciliation is the path of compassion, he says.

Mackay defines compassion not as an emotional state but a mental discipline, a commitment to treating one another kindly and with respect, “especially when we don’t agree with each other or don’t like each other, because compassion is the only rational response to an understanding of what it really means to be human”.

Christmas is a good time to discuss this, Mackay says, because it’s a person-by-person, street-by-street challenge. “I don’t think it’s a challenge for national leadership or for some grand strategy; I think it’s a matter of each of us saying ‘well we know this is what’s happening in our society, we are not mere bystanders in this. The mental health epidemic we face is our responsibility’.

“Go next door and make sure the neighbours are OK, invite people to have a Christmas street party, keep a close eye out for that frail elderly person living alone who’s at risk of social exclusion. It’s a highly personal case-by-case solution.”

When you believe yourself forgiven it is easier to forgive others.

John Dickson thinks things will get worse before they get better. “Societal breakdown may force us to see that unless there is something like reconciliation we are just going to tear each other’s throats out. That kind of breakdown in relationships may have to get worse before we realise that the only healing is in reconciliation that is willing to let go of the wound.”

He says there’s only so much breakdown we can stand before we realise we need a circuit-breaker, and reconciliation is the great circuit-breaker.

“The Christian narrative makes reconciliation a little easier. I’m not saying Christians are expert, but when you believe yourself forgiven it is easier to forgive others. That reconciliation comes because we know ourselves to be reconciled.

“We do not forgive because we seek forgiveness but because we have been forgiven.”

Barney Zwartz, a senior fellow of the Centre for Public Christianity, was religion editor of The Age from 2002 to 2013.

This article first appeared in The Age.