“I have always thought there might be a lot of cash in starting a new religion.”

How are religions born? This remark George Orwell made to a friend in a letter in 1938 appeals to our more cynical instincts: religions are birthed by charismatic individuals thirsty for wealth, power, fame.

Many a contemporary cult might fit that description (I tactfully decline to name any, including for legal reasons). The beginnings of our venerable world religions are more varied, though not less contested.

The visions of a prophet? The zeal of a reformer? Rituals and stories about the world that develop organically over time? However they started, the vast majority of people who’ve lived on this earth, and the vast majority of people who are alive today – perhaps 6.5 billion people – align themselves with a religion.

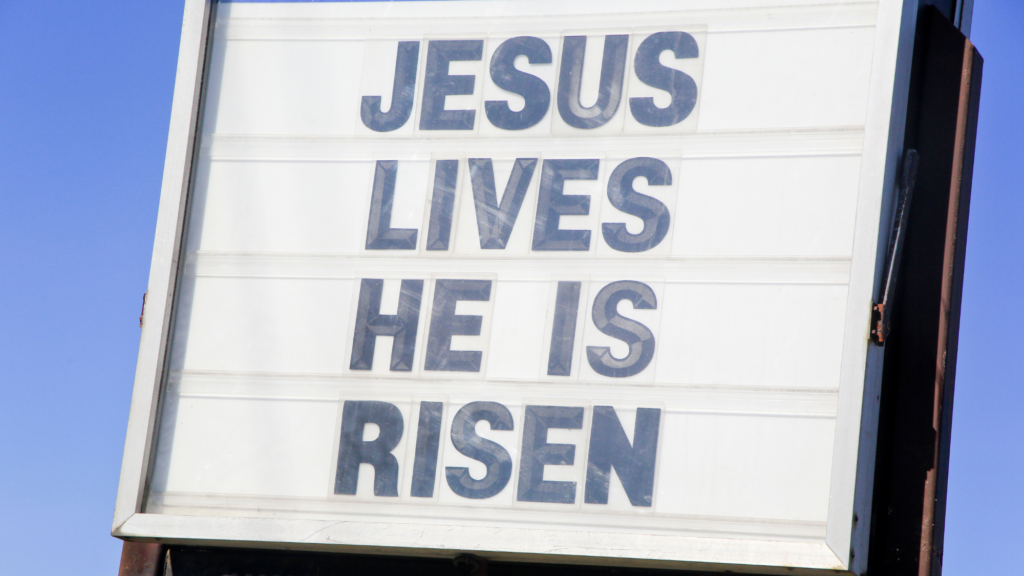

This weekend marks the weirdly specific beginnings of what remains the world’s largest religion, Christianity. The strangeness of Easter is that it hinges the entirety of a religion – the entirety of reality, by its own audacious reckoning – on a particular long weekend this one time in Judea.

The Friday crucifixion and Sunday resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth is a pivot point: earlier that week, Christianity does not exist. By breakfast-time Sunday, the first Christian evangelists have shared the distinctive Christian message for the first time: He has risen from the dead!

How unlikely a story was this? Let me count some ways.

Say you’re a charismatic drifter in first-century Palestine, on the hunt for wealth, power, and fame. Say you hit upon the idea of starting a new religion from scratch. It’s a highly religious world; there might indeed be a lot of cash in it, if you play your cards right. This Jesus fellow made quite a sensation locally – until the leaders turned the crowds against him and managed to get him executed by the state. Is this your chance?

Well, for starters, the getting-crucified thing is a definite spanner in the works. A dead martyr can be useful, but crucifixion was about the greatest humiliation the Roman Empire could inflict. In a world that worshipped military and political might, the story of a man who was God who was killed (especially like this) – a man who both preached and embodied meekness and humility – was going to be a hard sell.

Still, rising from the dead would be a pretty great twist. Perhaps enough to overcome the shame and horror of Friday’s unfortunate events. Obviously, dead people usually stay dead, so how would you convince people that something so incredible had actually happened?

You’re going to need some stellar witnesses. Which makes it awkward that in the accounts of Jesus’ resurrection, the first people to discover Jesus’ empty tomb and proclaim that he’s alive are … women. In the Jewish culture of the day, women’s testimony wasn’t even accepted in court in most cases. If you’re making this up, this is not the origin story you craft.

And then there’s the followers of Jesus. The twelve apostles are the ones who spend the next several decades fanning out across the Roman Empire and beyond, spreading this new religion – so presumably they must at least be in on the hypothetical fraud.

Humans love a good conspiracy theory. Also, we’re terrible at pulling off actual conspiracies. J. Warner Wallace, a celebrated cold case detective who decided to apply his professional skills to the accounts of Jesus’ resurrection, describes how difficult it is in reality – as opposed to the movies – to maintain a conspiracy for any length of time at all. People crack under pressure, and betray one another.

Warner Wallace says that successful conspiracies involve as few people as possible, for as short a time as possible, and with little or no pressure on the conspirators. Though he started out assuming that these guys concocted “the most elaborate and influential conspiracy of all time”, he soon realised: “I can’t imagine a less favorable set of circumstances for a successful conspiracy than the twelve apostles faced.”

The apostles’ extremely unlikely story about the events of that long weekend ended up getting far more traction with far more people than anyone could have anticipated.

These men stuck to the same message for years, decades, repeatedly facing arrest, torture, and the threat of death, not knowing if their fellow apostles had already given up the conspiracy elsewhere. Not one admitted the lie; almost all were killed for refusing to change their story, that they had seen the risen Jesus.

Warner Wallace concludes: “These men and women either were involved in the greatest conspiracy of all time or were simply eyewitnesses who were telling the truth. … While it’s reasonable to believe that you and I might die for what we mistakenly thought was true, it’s unreasonable to believe that these men died for what they definitely knew to be untrue.”

If the apostles were after wealth, power, and fame, their gambit backfired pretty badly. At the same time, their extremely unlikely story about the events of that long weekend ended up getting far more traction with far more people than anyone could have anticipated.

However you account for the origins of Christianity, and its explosive growth, all roads lead back to that three-day period in and around Jerusalem 2000 years ago. There’s a reason these events still mark our calendar: one way or another, this is the weekend that changed the world.

Natasha Moore is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and the author of The Pleasures of Pessimism and For the Love of God: How the church is better and worse than you ever imagined.