Content warning: . If you have trouble engaging with stories of abuse, please show caution before reading this review.

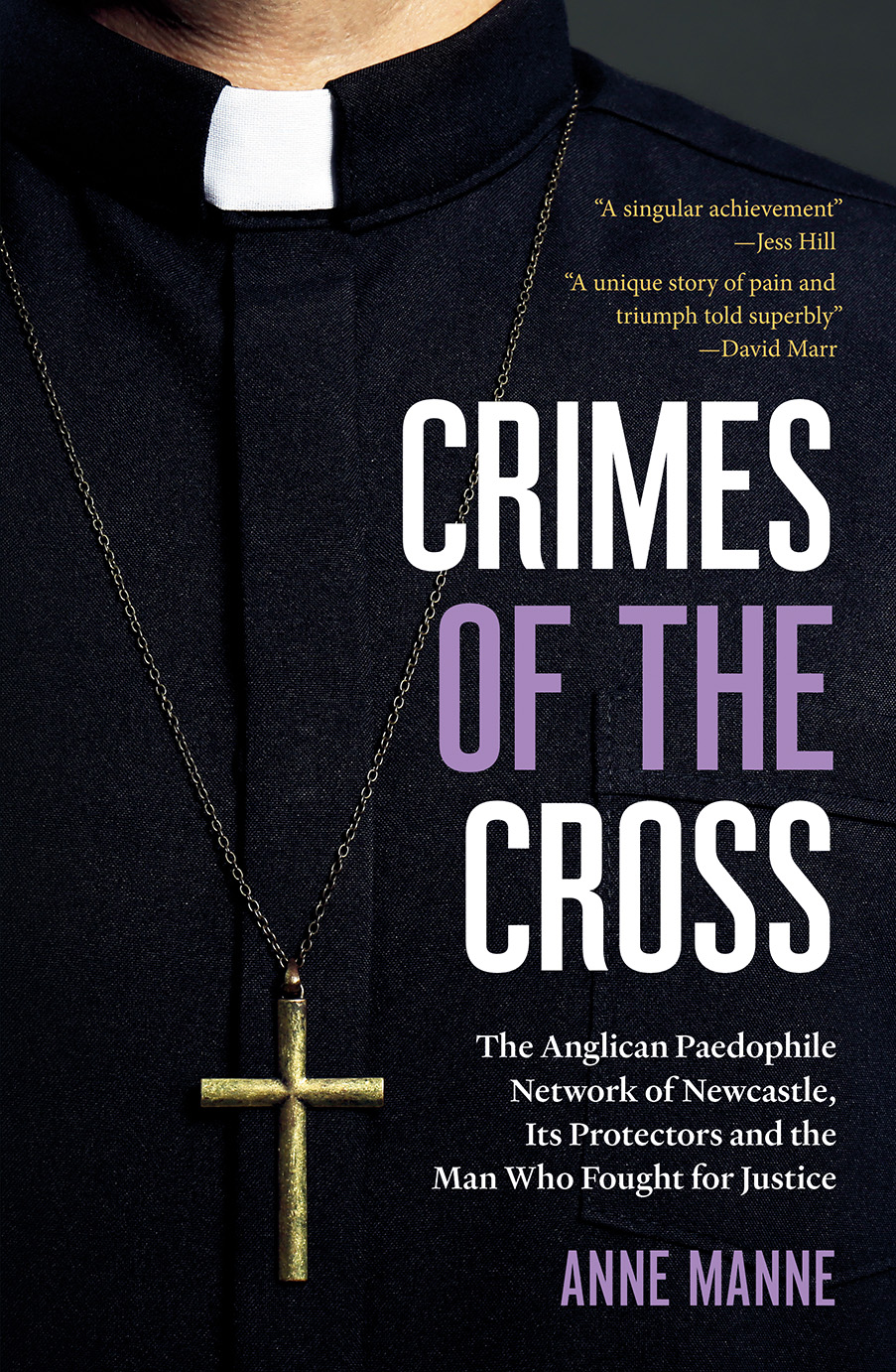

Crimes of the Cross

Anne Manne

Black Inc., $36.99

This book should come with a “horror” warning on the cover. In the ignoble annals of clergy sexual abuse in Australia, it is hard to top the Newcastle Anglicans for depravity and cruelty – of the perpetrators and, yes, of the hierarchy who knew what was going on for decades and cravenly allowed it to continue.

Successive bishops were strongly condemned by the royal commission into clergy abuse and one, Roger Herft – once spoken of as a possible head of the global Anglican Church who later became Archbishop of Perth – was even defrocked because of his failures. Had some earlier bishops of Newcastle been alive after the royal commission, they must have faced the same humiliation – Bishop Ian Shevill was actually an abuser.

Anne Manne’s harrowing account describes the abuse, how it flourished and was covered up, how the “halo effect” protected the abusers, and how accountability and justice finally arrived, if too late for many.

In particular, it is the story of Steve Smith, a remarkable survivor whose courage, perseverance, determination and finally compassion over the decades kept pulling up the carpet under which the diocese had tried to sweep its shame. Manne observes the Newcastle Anglicans included “some of the worst of the worst … it was soul murder of little children who struggled ever after with what was done to them”.

Steve Smith was a cheerful child who enjoyed what he called a Huckleberry Finn existence until just before his 10th birthday, when Father George Parker arrived at his parish. Parker immediately began grooming Steve’s whole family, winning their trust. The abuse started when Steve became an altar boy: Parker first bent him over and assaulted him outside his clothing. He would fondle the boy while driving him to different church services, then began digitally raping him before escalating to oral and anal rape.

Steve’s nightmare continued for five years, including being raped on the church altar, shared among priests, raped at orgies, and seeing other boys abused. He believed Parker that there was no point in telling anyone, condemning him to live day by day with his enormous, explosive, shame-ridden secret.

Later, seeking help from the church, he was repeatedly fobbed off. When he went to police, the investigation was obstructed by the entire church hierarchy, from the receptionist to the bishop, and especially the registrar, Peter Mitchell (later jailed for theft).

The leadership, both clergy and lay, were concerned only to protect the church and, for some, to continue their pleasures.

Here the long-time dean of Newcastle, Graeme Lawrence, was the key figure. Lawrence, finally jailed in 2019 for sexually assaulting a boy (he was paroled on April 10), was the fox in charge of the henhouse, the man responsible for overseeing the response to allegations.

According to Manne, Lawrence was a formidable networker, far and away the most influential cleric in the diocese, who cultivated civic, political, legal and social relationships. In so doing, she writes, “he effectively groomed a whole city”. He established a “halo effect”, “a reservoir of admiration and goodwill, whereby people see the abuser as beyond reproach, enabling them to hide in plain sight”.

Bishop Roger Herft was willing putty in the hands of people such as Lawrence. Herft was savaged by the royal commission, which simply did not believe much of what he said, and was deposed from Anglican holy orders in December 2021. Yet at the end of the hearing this most culpable of prelates finally seemed to grasp the seriousness of his failures. Manne records a touching scene after his evidence when he tremulously apologised to Steve Smith, who said he forgave him.

There were heroes too, church and police who believed and championed the victims, particularly business manager John Cleary, diocesan investigator Michael Elliott, who both received death threats among other unpleasantness, the Reverend Roger Dyer and Detective Jeff Lantle.

But things really improved when change came at the top in the form of Bishop Greg Thompson, himself an abuse victim who brought the experience, determination and authority to reform the diocesan responses to abuse complaints.

Manne relies heavily on the royal commission, surely one of the most important and effective investigations in Australian history, and its case study 42 on the Newcastle Anglicans, itself 400 pages long. But she has immersed herself in the diocese and in the victims’ stories.

Her narrative is all the more powerful for being mostly matter of fact and unemotional. She is too wise to gild the lily when it comes to the suffering of the victims and their supporters, a temptation to which some journalists succumb. The bald narrative contains all the power she needs, and I confess it brought me to tears several times.

The paedophiles and their protectors have done incalculable damage, first to victims then to the institution. The light Manne casts is therefore all the more valuable.

Barney Zwartz, a senior fellow of the Centre for Public Christianity, was religion editor of The Age from 2002 to 2013. This article first appeared in The Sunday Age.

National Sexual Assault, Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732).