“Don’t worry, you can’t crush a soul here … that’s what life on earth is for!”

For decades now Pixar has been making us — the adults in the room — laugh, think and also (if we’re honest) sob quietly in the corner. These puppet masters know their way around the human heartstrings.

And their films dive fearlessly into the really big questions: What makes life worth living? What makes us happy? What makes me me? How do you survive loss?

Here’s three things we’ve learned from watching these movies made (allegedly) for kids.

1. There’s more to life than success (Soul, 2020)

Pixar’s most recent film tells the story of Joe Gardner, a middle-aged, middle-school music teacher who has always dreamed of being a professional jazz musician. On the very day his ambition might be coming true – he lands his dream gig – he falls down a manhole on a New York street and finds himself on his way to the “Great Beyond”.

Joe, though, is not ready to move on. He claws his way back only to find himself in the “Great Before”, where souls receive their personalities, quirks, and interests before heading to earth. He hatches a plan to secure another shot at life by helping 22, a new soul highly sceptical that life on earth could be worth living, to discover her “spark”.

Both Joe and 22 assume that this “spark” is your passion, the thing you’ll be brilliant at – that your identity is founded on your talent, what makes you exceptional. For Joe, it’s music. 22 tries an array of options and concludes life just isn’t for her.

But ultimately, Soul insists, it isn’t what you can do that makes you special. Life itself is meaningful, even wondrous.

2. There’s more to life than happiness (Inside Out, 2015)

This fan favourite takes the chaos of what’s going on in our heads and turns it into a tug of war between five characters: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust and Anger.

These personified emotions operate the control desk in 11-year-old Riley’s mind, and find it bumpy going as she moves with her parents from a happy life in Minnesota to unfamiliar San Francisco.

Inside Out has lots of clever and sometimes hilarious insights into personality, memory (and forgetting), dreams, and how we think and feel. But its key lesson might be this one: sadness knows things.

Early on, Joy explains how Fear and Disgust help keep Riley safe, and Anger cares deeply about things being fair, but Sadness? “I’m not actually sure what she does.”

As Riley’s carefree life gets more complicated, though, Joy’s attempts to deliver uninterrupted happiness become increasingly neurotic. Sadness has most of the good ideas — she’s the one who’s read the “mind manuals” and who understands, often better than others, how things work.

There is wisdom, it turns out, in sadness. The relentless demand for happiness is self-defeating; the acknowledgement that things are not OK is much healthier.

3. There’s more to life than control (Up, 2009)

Once you’ve wept your way through the first 10 minutes of Up and (spoiler alert) the death of Carl Fredricksen’s wife Ellie, the quest part begins: fulfilling a lifelong dream he and Ellie shared since they were kids, Carl decides to travel to Paradise Falls in South America — by attaching a truckload of helium balloons to his house.

Things don’t exactly go to plan (and not because of the balloons, which prove a surprisingly efficient transport option). No, it’s other people (or creatures) who get in the way of Carl’s dearly-held plans.

First, he discovers that Russell, an eager young “Wilderness Explorer” who’s been trying to earn his “Assisting the Elderly” badge, has accidentally stowed away on the voyage. After landing, their attempt to walk the house over to the Falls before the balloons deflate is derailed by a huge colourful flightless bird and a golden retriever whose sinister master is determined to catch said bird.

The turning point for Carl comes when he turns his back on his new and unwanted friends in their hour of need, declaring: “This is none of my concern. I didn’t ask for any of this!”

A rich life is not about things going how they’re “supposed” to, but about those very interruptions and complications that expose the illusion that we are in control.

Of course, he soon discovers there are more important things than the plans we lay down for ourselves. A rich life is not about things going how they’re “supposed” to, but about those very interruptions and complications that expose the illusion that we are in control. And in particular, those we meet along the way who demand — and return — our love.

Do we buy the picture Pixar sketches for us of what it means to be human?

Going by the findings of the World Happiness Report 2021, it might be wise to do so.

Soul, Inside Out, and Up show us how crisis points can bring into focus what really matters. The extraordinary pressures of 2020 on a global scale show up not just in the tragedy of excess deaths but in overall drops in happiness: there was a roughly 10 per cent increase in the number of people who said they were worried or sad the previous day.

But the data comparing how different nations fared in wellbeing across 2020 also confirm what Pixar has been telling us: connectedness (including to pets) and trust in other people (including strangers) are more important than income, employment or even health risks when it comes to happiness.

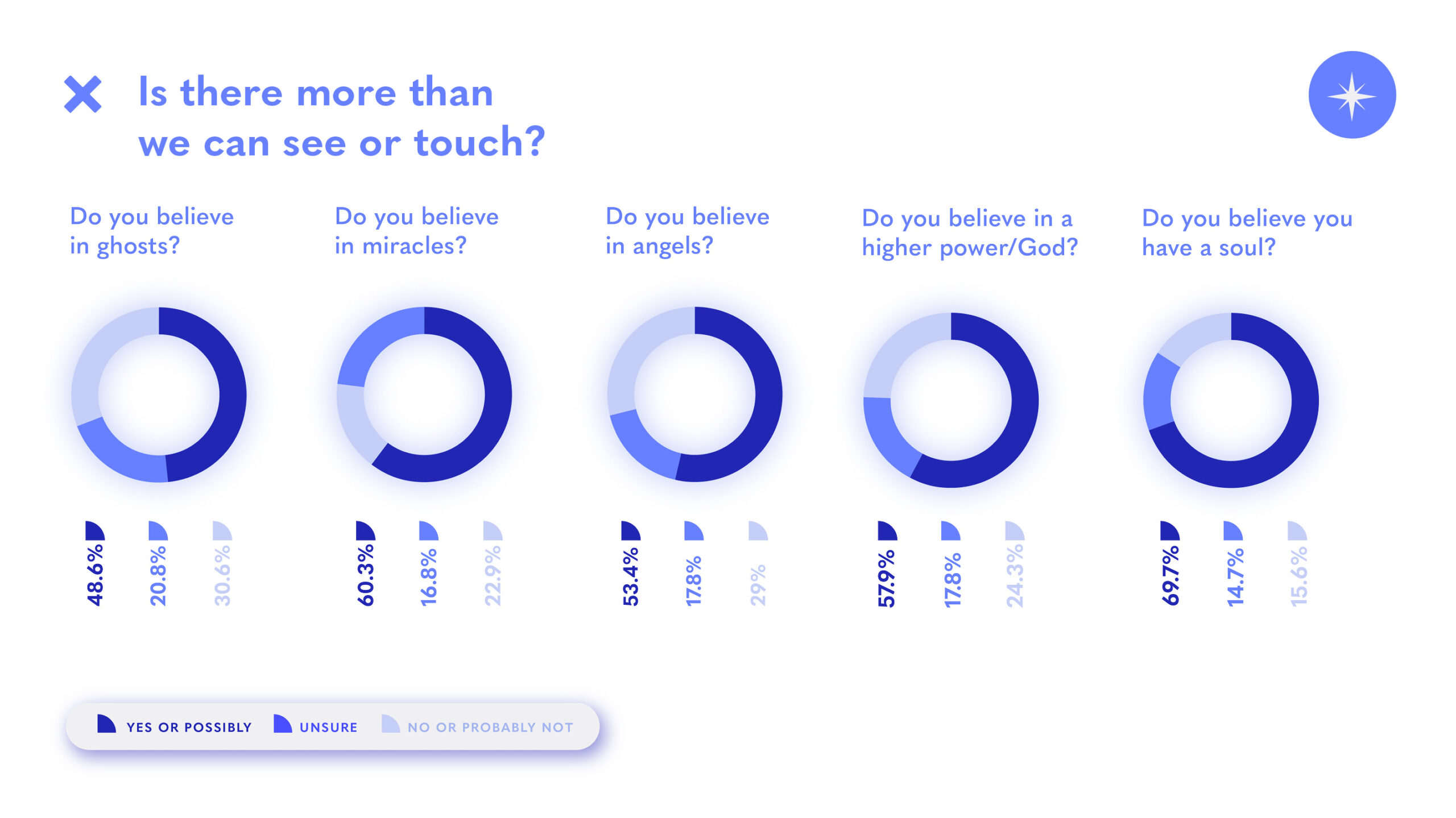

Do our beliefs about reality track with those findings? New data from McCrindle Research illuminates how open Australians are to certain ideas about life and the self.

44 percent say they believe in the soul. Include those who say they are open to the possibility, and that number rises to 69.7 percent.

Ultimate meaning or purpose in life? 64.3 percent say either yes or possibly.

Miracles (60.3 percent), life after death (59.6 percent), a higher power (57.9 percent): a majority of Australians, it seems, are at least open to the idea that there is “more” to life than the mundane or the material.

What that “more” might be is an open question. After the uncertainty of the past year, and in an ever-spiralling epidemic of anxiety, it makes sense that it’s a question we might be asking.

J. Richard Middleton, a theologian at Northeastern Seminary in New York State, explains that the idea of the soul is ancient – and why it continues to be attractive today:

“For Plato, I think, the notion of a soul was some point of stability and universality in the world. Because the world is a flux, everything is passing away, but the soul is this immaterial part of you that never changes – it just is you, and it’s eternal. I think people need something that’s beyond this world to cling to, something transcendent.”

Whatever form of transcendence we’re drawn to, it seems that Pixar repeatedly taps into an intuition many of us share: that life ultimately is not flat or empty, but animated.

Natasha Moore is the author of The Pleasures of Pessimism. She has a PhD in English literature from the University of Cambridge and is a Senior Research Fellow with the Centre for Public Christianity.

This article first appeared at ABC Everyday.