Gordon Menzies has been an academic and an AFES volunteer at the University of Technology Sydney since 2003. Prior to that he was an economist at the Reserve Bank of Australia. He is currently an Associate Professor in Economics, with an international research reputation and a national teaching reputation. He is a member of the Simeon Network for integrative Christian scholarship, and over the years has contributed to public debate in the ABC, the Guardian and at CPX. Mark Stephens interviewed him about his twenty-years-in-the-making book, Western Fundamentalism.

MARK: Thanks Gordon for joining us today. Tell us what are you up to right now in this season?

GORDON: Like most of my academic colleagues I’ve been teaching online and doing my best to stay out of everybody’s way. My overseas sabbatical was upended by Covid-19, but it did give me an opportunity to put the finishing touches on something I’ve been working on for twenty years.

MARK: You have been an Economics professor over that time, and you’ve written a book about philosophy, politics, religion, and sex. And then you went ahead and used the word fundamentalism in the title! Why is an economist writing about topics outside his field??

GORDON: Just trying to do my job, Mark. Economists are supposed to be efficient and I think I have found a way to save everyone from wasting time in the Culture Wars. The key idea is that when you are getting nowhere in a conversation a good question to ask is – Which of my fundamental beliefs would I need to change in order to agree with my conversation partner? This doesn’t necessarily mean changing your beliefs, but understanding where the crux of the conflict hides is a good way to move forward in a conversation.

My hope for this book is that it will help people answer that question. Part of that journey involves becoming aware of some of our own unexamined values, which is uncomfortable.

MARK: You think unexamined values operate in everything we do. Can you give us an insight into why you call them fundamentals, or this perspective we all have as “fundamentalism”?

GORDON: The phrase “Western fundamentalism” sounds like an oxymoron. At our most naive moments we think “Western” means rational and safe, while “Fundamentalist” means stupid and violent.

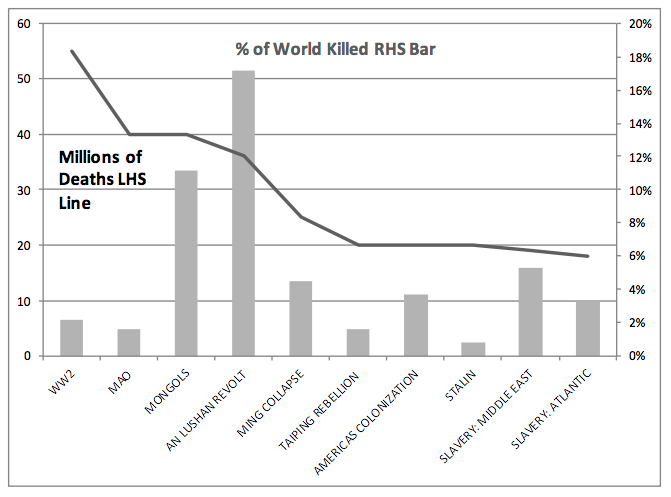

But, as I demonstrate in my first chapter, everyone – not just a religious fundamentalist – is in the position of basing their lives on something they cannot prove. If people whose intelligence and integrity you admire are doing this, then how can it be synonymous with stupidity? What’s more, the history of violent deaths is absolutely dominated by secular wars. So religious fundamentalists don’t have the lead role in the history of violence.

Let me share with you what set me off on my twenty-year journey. The Oxford Union is one of the world’s most prestigious debating societies, so when I was a student there, I naturally wanted to cut my teeth in these debates. To my surprise, however, I soon found myself getting bored because they seemed to boil down to political-legal superficialities. When I asked one of the leaders about this he immediately saw my point and said that everyone who came to the university believed uncritically in three things: democracy, free markets and sexual freedom. So here were these people who despised “dogmatic fundamentalists”, themselves holding certain uncritical fundamental beliefs! Over the years, Oxford has been one of the great founts of Western thought, so I began to wonder if this diagnosis applied to the rest of the West.

MARK: Are you saying there are faith commitments that lie at the base of all our thinking?

GORDON: Yes. Fundamentalism is a kind of a word parable. It tells a story that everybody, absolutely everybody, has what you call faith commitments embedded in their outlook on life. As you know from your study of philosophy, Mark, there was a time when people denied this. At the dawn of the 20th century, there was an unbridled confidence in human knowledge and progress – so much so that the futurists in Europe even used to write poems about machines! But that has unraveled in the 20th century. Two World wars humbled us all about progress, and, in philosophy, people began to question how easy it is to prove things. We now generally talk about a postmodern era, where the consensus is you can’t really prove everything you believe from a common set of beliefs held by all rational people. The early Fundamentalists were open about this and were openly despised. But history if full of irony. It is now accepted that basing your beliefs on some unproven assumptions isn’t just an option. It’s the only game in town.

MARK: So you spend a large amount of the book exploring ideas where we don’t think about their underlying assumptions. One such idea is democracy. You have a knack of exploring both what’s great about democracy but also explaining its inadequacies. What are those benefits and limitations?

GORDON: I think an undeniable strength of democracy is that it makes it difficult for a minority to oppress the majority. The votes would stack up against those in the minority to make it very difficult. Granting that, though, I think it’s important not to claim too much for democracy. You can get the most out of something by having a realistic idea about what it can achieve, not by imagining it can do more than that.

So I talk in the book about how democracy doesn’t automatically protect the weak and how it is powerless against mass delusion. If the whole culture believes in the justice of an unjust war or believes in some kind of practice which is morally wrong, then democracy doesn’t obstruct that cause, it actually strengthens it.

There’s a famous theorem developed by the French philosopher Condorcet about how groups can tap into the so called wisdom of the crowds. Let’s suppose that every person has a 70% chance of believing we landed on the moon and a 30% chance of believing it’s a fabricated story. Condorcet showed that if, instead of just selecting one person and asking them what they think, you randomly select three people and a majority vote wins, then the chance that the committees of three will affirm a real moon landing rises to 80%. But it runs the other way as well. The maths is identical when each person has a 70% chance of believing Donald Trump was a professor in women’s studies at Harvard before becoming president. If you form committees of three it will simply intensify the chance that this falsehood will be believed – in democracy three blind mice aren’t any better off than one – in fact they are worse.

MARK: So democracy relies upon a responsible, rational, and ethical voter. We often blame the politician but we struggle to sometimes blame the electorate.

GORDON: Yes, in April 2016 I wrote an article about Donald Trump and democracy. At that stage it was absurd to think he could win, but all the same I made the point you just made: ‘Democracy is no better or worse than the state of its decision-makers – the people – and so it is best thought of as a majority-driven political technology for birthing the spirit of the age, by creating laws and policies consonant with it.’

MARK: Within a number of your chapters you talk quite a bit about the importance of human dignity. Why, in the West, is human dignity such a crucial yet fragile idea?

GORDON: I think it’s a crucial idea because it is the basis for human rights. The idea that each person has an essence which is irreducibly human and, in some sense, equally shared provides a reason for treating every single person with dignity.

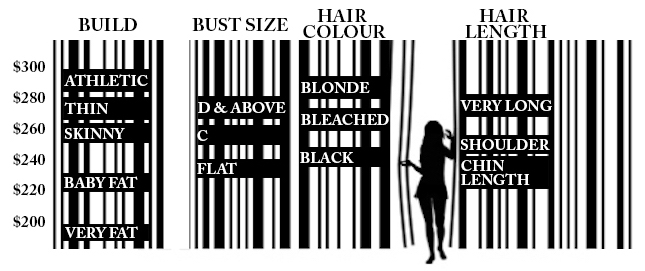

But in the book I discuss just how fragile our societal definition of dignity is, as you glance across the three fundamentals of western culture – democracy, free markets and sexual freedom. Dignity isn’t affirmed by market-based economics, nor by sexual freedom. It is affirmed in democracy partly because of the idea that each person has one, and only one, vote, no matter how financially successful or physically attractive they are. So it’s interesting to me that in the areas of the economy and sex, westerners can be so ruthless, but in the area of democracy they treasure human dignity.

MARK: So the contrast between democracy, on the one hand, and free market liberalism and sexual freedom on the other, seems to create a contradiction in our fundamentals?

GORDON: You are right on the money, and I think history has something to do with this. The Second World War was unfathomably tragic for the human race, but it did warn us what happens if you ignore human dignity in the political sphere. Unfortunately, in the other spheres of our economic and sexual lives we in the West have absorbed more of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche than we care to admit. He had a contempt for both weakness and the ideal of human equality. He felt they were corrupting influences in the West coming through the channel of Christianity, and we needed to return to Greco-Roman values which praised strength, beauty, and dexterity. So if you only value the strong and beautiful people, then you are actually diminishing the idea of each person having intrinsic worth.

MARK: As an economist you understandably speak to the role that money and prices and markets play in all of human life. This, for me, is one of the revelations of the book – the way that we apply “market” terms in so many different spheres. What is it that a regular person like myself doesn’t understand about the moral significance of economics?

GORDON: There are two moral concerns. Our economic system provides consumers with financial incentives to do some things that are directly damaging. For example, you can buy some goods cheaply even though those goods cause health problems, for workers or consumers. Since the goods are cheap, people want to buy them – but nobody ends up paying for the pollution or exploitation along the way.

There is a lot of evidence that being exposed to financial incentives actually forms your moral reasoning.

Something that concerns me even more than this is the ‘category creep’ of the economic system into our relationships. For example; are relationships no more than exchanges? Should you dispose of people when they no longer serve your interests like you would dispose of a piece of furniture? Do you only befriend people if they pass a “cost-benefit analysis” – that is, if the pros exceed the cons?

There is a lot of evidence that being exposed to financial incentives actually forms your moral reasoning. In one study, there was a group of creches in Israel that were having problems with parents turning up late. They decided to put in a financial penalty for being late, and the incidence of being late dramatically increased! Why?

Before the financial penalty, people saw turning up late simply as bad behaviour, they saw it as a moral issue. But once there was a price involved, their relational empathy was swallowed up by the transactional mindset of a cost benefit analysis – and they decided it was worth it to pay the fine and work longer hours at their high-paying job. Economists call this motivation crowding out, and in my public lecture in Oxford after the Global Financial Crisis I discussed its role in tipping the world into the crisis. Apparently, some bankers began to feel that truth-telling was subject to cost benefit analysis, and they should only do so when the pros exceeded the cons. Cost benefit analysis has its place, but it is dangerous when it dominates our morality completely.

MARK: So putting a price in places where traditionally we would say that’s not something we could put a dollar value on causes your entire behaviour to change. One of the areas that you really look at this is the Western view of sex. Gordon, people would say that love should never be about money, so why write a chapter on sex and economics?

GORDON: I said a moment ago that market-based economics has these two dimensions of concern. One is monetary incentive, and the other is when markets form our underlying moral reasoning.

As far as the incentives go, sex is now more easily ‘bought’ than it used to be through cheaper prostitution and pornography. This is well-known and the subject of extensive comment.

But, more profoundly, I want to add that our underlying attitudes to relationships have taken on a kind of market mentality. Perhaps I can quote from Stephanie Coontz who writes very beautifully about this. She is the author of Marriage: A History, and certainly not a conservative in any sense. But here’s how she feels as a woman in the modern world:

As a modern woman I live with an undercurrent of anxiety that was absent from the diaries of earlier days. I know that if my husband and I stop negotiating, if too much time passes without any joy, or if a conflict drags on too long, neither of us has to stay with the other.

She is referring to the idea that Westerners use people like they use things, and when they’re no longer passing a cost-benefit analysis, it is time to move on. This leaves women, and not a few men, feeling insecure.

It’s my conviction that many social commentators have missed the significance of this. They have accepted a narrative that the Sexual Revolution has been fueled by a Left-wing desire for social justice. But that’s only half the story – the other half is that the Sexual Revolution is a triumph of a Right-wing economic principle of market de-regulation creeping into our relationships, and the explosion of a market-based ethic of sexuality. Think of the relational disposability inherent in the Tinder culture – swipe Right for more.

MARK: Yet the language of thinking about relationships as a product feels jarring.

GORDON: It ought to. It is a kind of consumerism applied to people.

MARK: You use these three topic areas of democracy, economy and sex as insights into the core values that you’ve seen operating in the West. But you’ve also done something broader than that. You’ve actually considered why we think this way. Is anyone or anything particularly responsible for why we have set this course?

GORDON: I have nominated John Stuart Mill as the prophet of Western Fundamentalism. Mill is famous for the idea that we should do whatever we like as long as we don’t impact on anybody else. Now that’s exactly how we like to imagine ourselves in the West – pursuing our desires and dreams without any bad consequences for anybody. It may sound great to some, but it fails to recognize that we live in a very interconnected world and what we do actually does impact on others. There are very few situations where actions don’t potentially hurt anybody at all.

For this reason, we need more than Mill offers to explain the Western mindset – his principle covers so little of the ground in real social life. So I nominate Friedrich Nietzsche as a kind of high-priest of Western Fundamentalism. Nietzsche, as you know, is famous for his atheism, nutshelled by ‘God is dead’ but expanded in this quote:

We philosophers and free spirits feel, when we hear the news that the old God is dead, as if a new dawn shone on us. Our hearts overflow with gratitude, amazement, premonitions expectation – At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an open sea.

But Nietzsche’s optimistic utopianism here jars hard with his raging elitism. He thought that if someone has to get hurt in society, the moral principle is that the powerful and beautiful have a right to hurt the weak. He felt it was up to the ‘lovers of knowledge’ to freely choose their values, but he himself longed for a return to the Greco-Roman ethos. He even directly said that selfishness was a good thing. I quote again:

Whether one be servile before gods and gods kicks or before men and stupid men’s opinions, whatever is servile it spits upon, this blessed selfishness.

MARK: You’re never bored when you read Nietzsche.

GORDON: Nietzsche earns his office as high-priest through the immense consequences of his ideas on our thinking today, not only because of his attitude to the weak, and the way that’s expressed in sexual and economic freedom, but also because of his atheism. I think it’s a continual secularisation which helps Western Fundamentalism flourish. After all, Nature abhors a vacuum, and in the absence of Christian sources of values, neoliberal market-based values become very attractive.

MARK: So you have proposed Mill as at least one of the people who has had at a significant impact on us. In your book you make a distinction between Freedom From and Freedom For and claim that Mill was concerned more about Freedom From. You also point to the fact that the notion of freedom from constraint, only draws its fullest meaning when you also have a freedom for something, a goal, a destination. Do you see that western culture has a goal in mind for its freedom? Are you hopeful that western culture could develop a compelling vision of what freedom is for?

GORDON: I don’t feel Western culture has a compelling destination for its freedom, what I call Freedom For. Western freedom is about Freedom From anyone or anything that dares to tell us how we should live. So yes, I see Western freedom being primarily about freedom from constraint, with the crushing burden of inventing a meaning to sustain your entire life placed upon the individual. There is a lot of optimism in the project of ‘self-actualization’ or ‘self-expression’ as a means to carry this out, but I know I’m not alone in feeling that this is an investment with diminishing returns.

There is something restful to the soul in being given an identity, not having to restlessly invent, perform, earn and uphold one.

It saddens me to see the existential fatigue in the faces our youth. They’ve inherited the worst of this mentality, and I wonder if our upward trend in youth mental illness reflects it. There is something restful to the soul in being given an identity, not having to restlessly invent, perform, earn and uphold one.

Speaking as a Christian I think the two most important kinds of freedom are Freedom From sin – Jesus famously said whoever commits sin is the slave to sin. But it doesn’t end there – our Father offers us Freedom For full participation in His loving family, a seat at His table, and a key to His home. So I think there’s a beautiful given-ness in human nature which means human flourishing, Freedom For, is paradoxically found in obedience to God’s ways rather than us trying to reinvent what it means to be human.

MARK: Well if the goal of the book is to start better conversations then it certainly hit the mark for me. It made me think about what I believe consciously, but also about what I believe in areas that I often don’t consciously thing about. Is that the intended result?

GORDON: Yes, perhaps I should have entitled it ‘Winning the Culture Wars’ where winning doesn’t necessarily mean overpowering your opponents; it means loving them by understanding them, and yourself, better.

MARK: Thanks for joining us today Gordon.

Western Fundamentalism is available at Amazon in Australia and the US.