Creation can be an ugly topic of conversation—it seems to bring out the worst in people, the most intolerant, one-eyed, angry diatribes about evolution and dinosaurs, or about the earth being made in 4004BC according to some bloke called Archbishop Ussher. That kind of talk really isn’t my cup of tea.

But talking about creation doesn’t need to be about whether the world was created in six days or over billions of years. There are plenty of other aspects of creation and creativity to talk about.

But talking about creation doesn’t need to be about whether the world was created in six days or over billions of years. There are plenty of other aspects of creation and creativity to talk about.

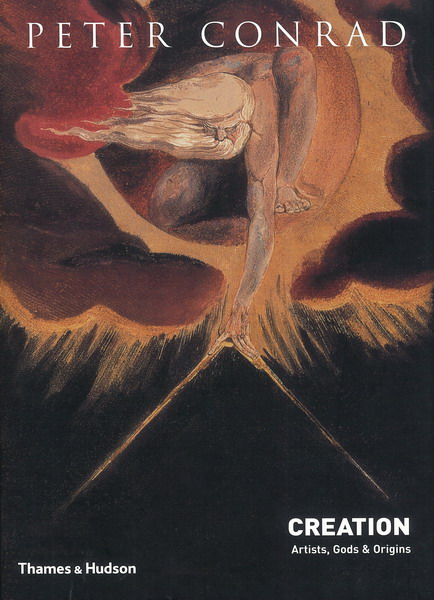

Oxford academic, Peter Conrad (a former Tasmanian) gives us 600 pages worth of other things to say about Creation in his extraordinary book, Creation: Artists, Gods and Origins.

He takes the broadest possible approach to the topic, writing a majestic narrative about everything to do with creation⎯making, generating, birthing, evolving, dancing, performing and even destroying. He writes about creation in painting, music, poetry, philosophy, in the history of science, current affairs, as well as in religion.

His book is a pleasure to read, although how one person has managed to cover such an expansive field, I really cannot fathom. But in the end, Conrad has written a book that is just as opinionated and singular in perspective as any fundamentalist tract.

Creation, for Conrad, is the magic of the artist, the wonder of the inventor, the unexpected discovery of the scientists, the seemingly miraculous feats of the dancer. Creation is something that describes the spirit of humanity. But, he argues, it is wrong to attribute creation to God.

He writes in his introduction: ‘This book is a celebration of art that doubles as a critique of religion’. So while the book celebrates the genius of human creativity, it also complains about and opposes any interpretation of human achievement or human understanding that reverts to the God hypothesis. In this book, God the Creator is the enemy. Conrad thinks that the idea of a divine creator, especially the one expressed by the biblical book of Genesis, has held back a proper appreciation of humanity’s own creative spirit.

Conrad seems to be annoyed with the biblical God, but I suspect he hasn’t given this God a fair hearing. He expresses anger at God for giving Adam and Eve free will and then berating them for eating the forbidden fruits. He writes, ‘the God of Genesis created men only to give himself the pleasure of tempting and ensnaring them’ (p.27). But I struggle to construct such a malicious deity from the pages of my Bible. A more sustained reading of the Bible, moving from Genesis through to Revelation, will give you a more satisfying picture of God and his relationship with the creation.

Conrad also sets up a false contrast between a bountiful vision of the world in mythology and paganism and a Christian vision that he thinks is all about denial and dullness. He writes:

| We are left with a choice between two versions of creation. On one side is the endless, self-replenishing nature of Hesiod, Lucretius and Ovid; on the other is a Christian society which arduously toils towards salvation, hoping to find redemption before it is uncreated by God’s second coming. (p.66) |

That simply isn’t the Christian vision of the creation and its future. The genuine biblical vision is far more like a feast, or like gift-giving at Christmas, than it is like some sort of trial or marathon. It is aesthetically delightful and exciting, not ascetic, uninspiring drudgery. And yet, so much of Christian practice has in fact been dour, bitter, boring and bland that I find it difficult to blame Conrad for reaching the conclusions he does.

Conrad has written a grand but blinkered account of Creation. The Christian vision deserves more serious reflection than Conrad is willing to offer. There is another cultural history of Creation to be written, one that does not take as its guiding thesis the ‘uncreating’ of the biblical deity. There is a history of Creation that celebrates the place of God the loving Creator in not only the causing and superintending of the physical world, but also in nurturing the human creature as he or she goes about marvelling at this world, adding to it and rearranging it with works of art, science, engineering and medicine. That’s the kind of Creator and Recreator I believe to be at work.

Dr Greg Clarke is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and Macquarie Christian Studies Institute