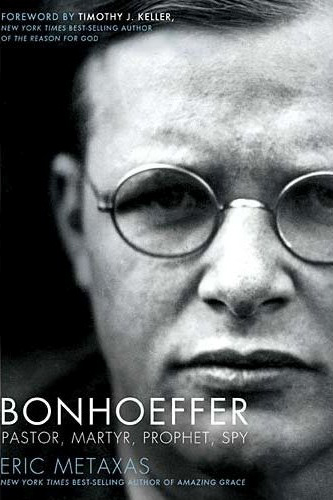

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd described Dietrich Bonhoeffer as the man he most admires from the twentieth century. What’s so admirable about Bonhoeffer? Reading the 550 page Metaxas biography answers this question in full.

Bonhoeffer’s life was a mixed genre. It started out like a fairy tale. Born in 1906, along with his twin sister Sabine, the sixth of eight children, his family had been prominent in German society for centuries, with many doctors, lawyers, judges and professors among his ancestors.

Dietrich’s father was a professor of Psychiatry. His mother studied piano with the famous composer Franz Liszt. His older siblings became or married professors, scientists and lawyers. The family home was a mansion in a beautiful forest of birch trees complete with a tennis court, orchard, huge garden, a menagerie of animals and half a dozen domestic staff. The reception room had a grand piano, oriental carpets and paintings of the Alps and famous relatives by famous relatives.

Dietrich became a Christian pastor and lecturer and a leader of the church in Germany. He was a tall man, with an athletic physique, and a round boyish face. With his mother’s blue eyes and blond hair, he fitted perfectly Hitler’s Aryan stereotype. However, any affinity between Dietrich and the Third Reich stopped there.

With Hitler’s rise to power the fairy-tale took a dangerous turn, transforming into a spy thriller. For more than a decade he worked for the good of his nation, eventually operating as a double agent. Employed by the Abwehr, a division of German Intelligence, Bonhoeffer used his contacts outside of Germany to support the insurgency. In particular, he briefed a member of the English House of Lords and convinced him to seek favorable terms of peace in the event of the Führer being removed. A man of impeccable integrity, Bonhoeffer also functioned as the conscience of the conspirators, commending their moral courage and bolstering their resolve.

Along with the spy thriller, Bonhoeffer’s life was a tragic love story. In June 1942 Dietrich met Maria von Wedemeyer. Maria was beautiful, poised, fresh, cultured and filled with vitality, but only eighteen years of age, fully seventeen years younger than Dietrich! Dietrich and Maria fell in love. Maria’s father had been killed on the Russian Front and her mother insisted on a year’s separation to test the couple’s feelings. Maria convinced her mother otherwise and in January 1943, with some restrictions in place, they were engaged to be married.

Unfortunately, ‘happily ever after’ is not the way the story ended. Just a few months later, Dietrich was arrested by the Gestapo and incarcerated for two years. Just one month short of the end of the war he was executed on direct order of Adolf Hitler. His parents learned of his demise a few months later listening on the radio to a memorial service held in London.

Metaxas covers all of this and more in compelling detail, skillfully drawing Bonhoeffer’s portrait against a backdrop of mid-twentieth-century European history and Continental theology. With co-conspirators with names as captivatingly cool as Henning von Tresckow, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin and Fabian von Schlabrendorff, there is plenty to keep the reader engaged! The coverage of Bonhoeffer’s life is comprehensive, ranging from his travels and education, family relationships, close friendships, and love life, to his thinking about ethics and theology, his uncanny prescience, and his ecumenical and political activities. Bonhoeffer emerges as a highly intelligent and gifted man of great courage.

Dietrich certainly had a way with words. He was a prolific author and is still highly regarded in the academic world for his original and sometimes radical thinking. But he also had the common touch. How does a person of faith justify being involved in plotting assassination? Bonhoeffer reasoned that if an out of control drunken driver were killing pedestrians on a main street like the Kurfurstendamm Strasse in Berlin, it would be the responsibility of everyone to do all they could to stop that driver from killing more people. At one point Bonhoeffer was pressed to join the state-sponsored “German Christian” church that had bought into the nationalist Nazi dream for the nation. Bonhoeffer refused, and quipped that it is pointless to board the wrong train and run down the corridor in the opposite direction.

For all his worldly wisdom Bonhoeffer held to orthodox Christian beliefs, including salvation by the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ and our own resurrection from the dead. He wrote: “Death is hell and night and cold, if it is not transformed by our faith. But that is just what is so marvelous , that we can transform death.”

For all his worldly wisdom Bonhoeffer held to orthodox Christian beliefs, including salvation by the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ and our own resurrection from the dead. He wrote: “Death is hell and night and cold, if it is not transformed by our faith. But that is just what is so marvelous , that we can transform death.”

Does Metaxas ignore Bonhoeffer’s failings? He does mention the less agreeable personal qualities of his subject. Apparently Bonhoeffer sometimes came across as aloof, snobbish and even bad tempered. But each of these seems to fade in the light of his exemplary dealings with others. Against all custom he worked at a black church while a student in New York. And in Berlin he ran a confirmation class for fifty underprivileged boys, visiting every one of them in their homes and renting a furnished room in their neighbourhood in order to socialize more readily with them.

Bonhoeffer is based on painstaking historical research. It is well-written, historically illuminating and intellectually challenging. It builds on, extends and sometimes corrects previous accounts of Bonhoeffer’s life and thought. Eric Metaxas is to be congratulated for writing a stirring and challenging biography.

Christians are sometimes rightly criticized for being so heavenly minded that they are of no earthly good. Bonhoeffer’s life proves that this does not have to be the case. He held together things that others mistakenly assume to be mutually exclusive. Bonhoeffer believes in both divine sovereignty and responsible action, both bold deeds and gracious forgiveness; both caring deeply and not despairing, both loving this world and eagerly anticipating the next. He believed that he was not the author of his own life. Yet that didn’t stop him from dreaming and yearning and hoping and working. The day after one of the plots to kill Hitler failed, he concluded, “[it is] only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith.”

Dr Brian Rosner is a CPX Fellow and Lecturer in New Testament and Ethics at Moore Theological College. He is the author of a number of books including Beyond Greed