The historian, theologian, musician and physician – Albert Schweitzer, single-handedly overturned the strident scepticism of Enlightenment scholars such as Reimarus and Wrede. Schweitzer’s 1906 volume The Quest of the Historical Jesus demonstrated that the portraits of Jesus offered by the supposedly objective historians of the previous two hundred years were basically ‘projections’ of what they themselves believed to be the ethical ideal. The characterization of Jesus as a simple, noble teacher, for instance, does not arise from the evidence, he argued, but is a construct born of the humanism of the Enlightenment. Such a Jesus is a figment of the scholarly imagination or, as Schweitzer himself put it, ‘a figure designed by rationalism, endowed with life by liberalism, and clothed by modern theology in an historical gab.’ Once Schweitzer had made the point, it was impossible to read Enlightenment scholarship without seeing projection on every page.

The Second Quest: the 20th-century recovery

After Albert Schweitzer there was almost fifty years of conspicuous silence on the subject of the historical Jesus. Between 1906 and 1953 the topic received very little attention in academic circles. The Enlightenment confidence on the matter had been crushed, and no one quite knew what to do with an ‘apocalyptic Jewish prophet’.

Karl Barth (1886-1968) and Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976)

Theologians during this period of hiatus tended to approach the Gospels in an a-historical way, almost as if the events of 5 BC—AD 30 were peripheral to Christian faith and life. Jesus had died, of course.

Theologians during this period of hiatus tended to approach the Gospels in an a-historical way, almost as if the events of 5 BC—AD 30 were peripheral to Christian faith and life. Jesus had died, of course.

No one doubted that. Indeed, for theological giants like Karl Barth and Rudolf Bultmann the death of Jesus is just about all that mattered for theology. Things like Jesus’ birth and healings—and even his teaching—were thought to be inconsequential for modern faith.

For Bultmann, especially, the really important thing about the Jesus story is that behind the ‘mythical garb’ lies a divine call to an existential decision—to say ‘yes’ to God.

If that sounds a little esoteric, remember, the 1920s-40s were the highpoint of the philosophy of Existentialism. Looking back on this retreat from history the German scholar Günther Bornkam opened his 1956 volume with this rather wry observation:

In recent years scholarly treatments of Jesus of Nazareth, his message and history, have become, at least in Germany, increasingly rare. In their place there have appeared the numerous efforts of theologians turned poets and poets turned theologians.

The ‘New Quest’ of Ernst Käsemann (1906-1998)

It was only a matter of time, however, before the pendulum began to swing back (slowly) to a renewed appreciation of historical questions about Jesus. And it was one of Bultmann’s most famous students who got the ball rolling again.

In 1953 Ernst Käsemann , a professor in Gottingen (moving later to Tübingen), gave a lecture titled ‘The Problem of the Historical Jesus’ in which he raised a question which over the last 50 years has received an increasingly positive answer.

Does the church’s image of the crucified and risen Christ find any grounding in the life and teaching of the earthly Jesus? Put another way, how much of the Gospels’ pre-Easter story supports Christianity’s post-Easter faith? It was a modest question but it signalled the rise of a more measured and productive approach to the question of Jesus.

how much of the Gospels’ pre-Easter story supports Christianity’s post-Easter faith?

The movement inspired by Käsemann is often called the ‘New Quest’ or ‘Second Quest’ for Jesus. It includes such significant names as Günther Bornkam, Norman Perrin and Ernst Fuchs.

Following Käsemann these scholars devised rigorous tests for working out what is ‘historical’ in the Gospels and what is not. One such test is called the ‘criterion of dissimilarity’ and it highlights something of the character and limitations of this new quest (which in some ways continues today).

The criterion of dissimilarity

The criterion of dissimilarity states that only things in the Gospels that are different from both Judaism, on the one hand, and the early Christian church, on the other, can be confidently said to have come from Jesus. The logic went like this: teachings of Jesus with strong parallels in Judaism could easily, so it was thought, be the result of the Gospel writers trying to make Jesus fit with the Jewish culture of their day; and teachings of Jesus with strong parallels in early church practice could be attempts to justify certain ecclesiastical traditions by having Jesus say it first. Hence, only things that are doubly dissimilar (from Judaism and Christianity) reliably come from Jesus.

Let me offer two examples of how this test is thought to sift out the ‘historical’ from the ‘unhistorical’ in the life of Jesus.

Jesus famously insisted that we must not swear oaths; instead, our ‘yes’ should mean yes and our ‘no’ no. This teaching is radically different from Judaism in the first century and the later practice of the early church—both continued to affirm the use of oaths. Since it is unlikely that the Gospel writers would invent something so dissimilar from Jewish and Christian culture, this teaching is regarded as authentic.

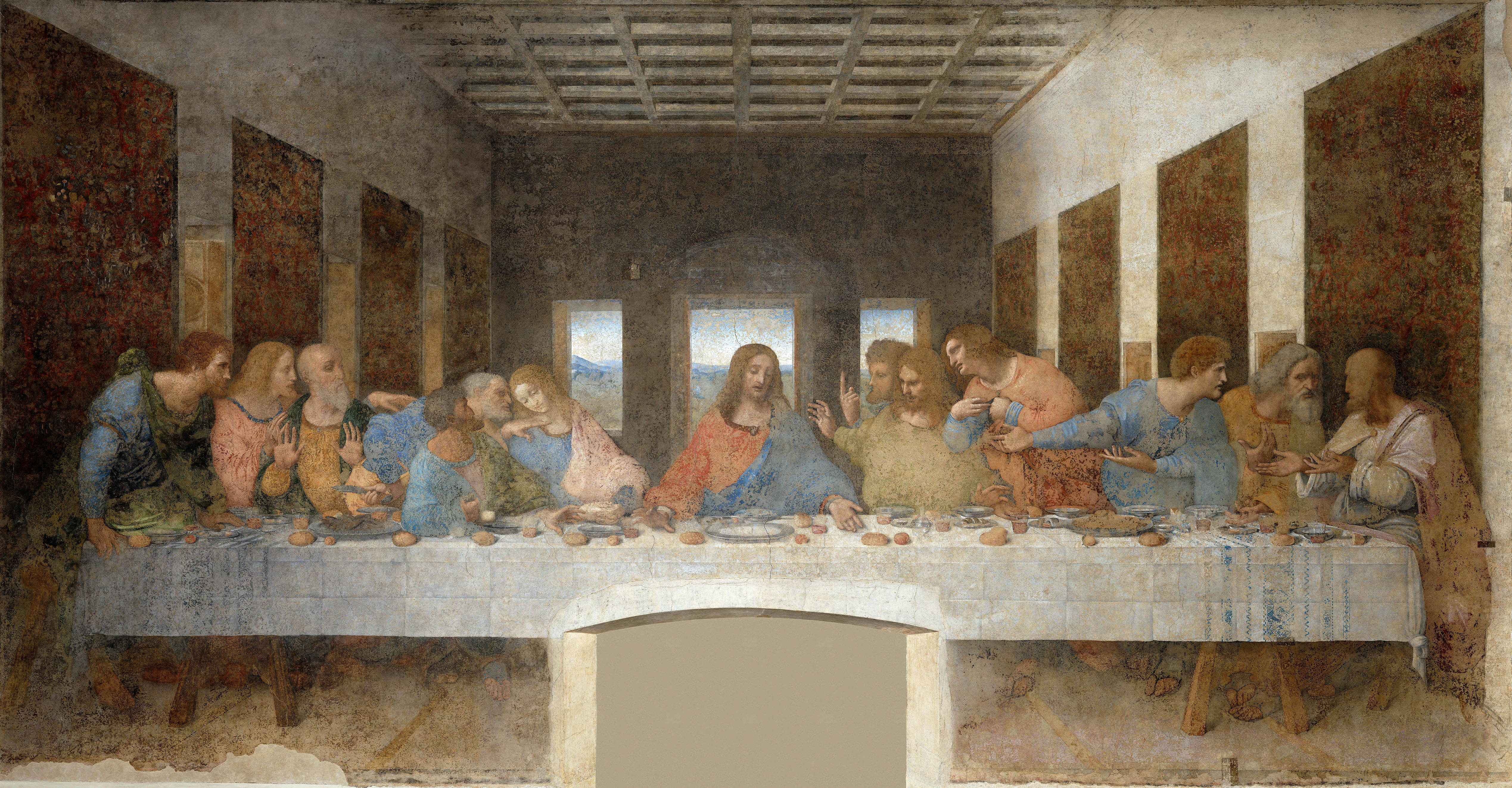

Now for a negative example: The famous Last Supper of Jesus obviously has strong affinities with the church’s later Lord’s Supper ritual. It may therefore be an invention designed to ground a later ceremony in the life of Christianity’s founder. It also has a lot in common with the Jewish Passover festival, the highpoint of the Jewish calendar. Perhaps, then, the Gospels are simply trying to make Jesus sound more Jewish at this point. The Last Supper is thereby called into question by the criterion of dissimilarity.

How could the historical Jesus not have sounded Jewish!

Contemporary scholars have severely criticized this particular test for historicity. For one thing, suggesting that something is authentic only if it was not picked up by the early church, assumes that Jesus had no lasting impact on his followers. This is plainly ridiculous. Author after author in the New Testament affirms Jesus as the foundation of the Christian life.

Just as strangely, the suggestion that ‘Jewish sounding’ teachings are unhistorical ignores one of the most obvious details of Jesus’ life. He was a Jew living in Jewish Palestine.

How could the historical Jesus not have sounded Jewish! The harshest criticism comes from the pen of the great Jewish scholar Professor Geza Vermes of Oxford University:

|

How, then, can anyone imagine that a saying of Jesus, in order to be authentic, had to distance itself from every known expression of ‘Jewish morality and piety’? Such an angle of approach is quite close to the old-fashioned anti-Semitic attitude according to which the aim of Jesus was to condemn and reject the whole Jewish religion. |

The ‘Jesus Seminar’ and the Second Quest

There are still scholars operating today in the mode of the Second Quest. The so called Jesus Seminar is a group of American scholars led by Robert Funk. Members of the Seminar continue to apply the criterion of dissimilarity and other tests, and then vote on whether a certain saying or deed of Jesus is authentic (they literally get together and take votes). The result is a conglomerate of the Gospels published for the popular market in 1993, complete with colour-coding: black text for the parts that definitely did not come from Jesus, grey for those that probably did not, pink for the things that may well correspond to something he said and red lettering for ‘the authentic words of Jesus.’ Needless to say, very little red ink was required in the printing.

the Jesus that emerges from the Jesus Seminar is un-Jewish, uninterested in a future kingdom and a perfect model of democracy, equality and freedom. He very much resembles the neo-liberal Christian academics who have devised him

In a manner that few mainstream scholars would accept, the Seminar also emphasizes alternative Gospels, particularly the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas. In these Gnostic Gospels, which we will explore later, Jesus is stripped of his Jewish identity and his preaching of a future kingdom and appears instead as a simple teacher of universal wisdom. Unsurprisingly, the Jesus that emerges from the Jesus Seminar is un-Jewish, uninterested in a future kingdom and a perfect model of democracy, equality and freedom. He very much resembles the neo-liberal Christian academics who have devised him. The Jesus Seminar should be haunted by Albert Schweitzer’s critique of 19th-century versions of Jesus—‘a figure designed by rationalism, endowed with life by liberalism, and clothed by modern theology in an historical gab’—but it isn’t. ‘Jesus has once again been modernized,’ writes Professor James Dunn of Durham University reflecting on the efforts of the Jesus Seminar, ‘or should we rather say, post-modernized!’

The Third Quest: significant advances in contemporary scholarship

Most scholars today are deeply sceptical about the methods and conclusions of the Second Quest just described. Divorcing Jesus from his first century Jewish context amounts to a serious historical blunder, akin to trying to assess the life of Napoleon Bonaparte by ignoring 18th century European philosophy and politics.In recognition of this deficiency many scholars have called for a new quest, the so called Third Quest (following on from the flawed quests of the Enlightenment and the mid-20th-century).

Over the last 30 years a massive industry of academic literature has sprung up around the figure of Jesus. It does not all speak with one voice but there is a wide consensus on at least one significant thing. The surest first-step toward discovering the historical reality about the man from Nazareth is to locate him firmly in his first century Palestinian environment.

The publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls—first found in 1947 but becoming widely available during the 1980s and 90s—has aided this effort to see Jesus in his Jewish context. The Scrolls have deepened and widened our picture of Judaism in a way that was impossible before.

Two scholars deserve special mention, and many others stand in their wake:

Martin Hengel (born 1926)

Martin Hengel has been Professor of New Testament and Ancient Judaism at Germany’s prestigious University of Tübingen since 1972 (he is still there as Professor Emeritus).

In some ways Hengel was part of the mid-20th century quest launched by Ernst Käsemann. In writing after writing he has applied a rigorous historical method to uncovering the connections between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith. But there is one major difference. Whereas others in the 20th Century Quest downplayed the connections between Jesus and Judaism, and still others sought to play up the connections between Jesus and pagan religion, Hengel resolutely set out to clarify our picture of first century Palestine, and then to set Jesus and the Gospels within that assured context. It was Hengel who wrote the definitive account of the rise of Jewish revolutionaries in the first century (known as the Zealots). It was Hengel who wrote the brief but unsurpassed history of crucifixion in the New Testament period. And it was Hengel who clarified for scholars the relationship between first century Judaism and the surrounding Greco-Roman environment.

He demonstrated that all of the New Testament descriptions of Jesus come from Jewish traditions (not pagan ones) current in Jerusalem in the period of Jesus himself

Because of his peerless knowledge of the Jewish (and Greco-Roman) context Hengel has also been able to write books of lasting significance directly on the topic of Jesus. In The Charismatic Leader and his Followers he refuted the suggestion of theologians like Rudolf Bultmann that the early church proclamation of Christ had little to do with the historical ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. In The Son of God he overturned the notion, popular at the time, that Christian beliefs about a ‘divine son’ derived from pagan myths. He demonstrated that all of the New Testament descriptions of Jesus come from Jewish traditions (not pagan ones) current in Jerusalem in the period of Jesus himself.

Ed Parish Sanders (born 1937)

Perhaps the key figure in the Third Quest is Professor Ed Sanders of Oxford University in the UK and now Duke University in the US. Like Hengel, Sanders is an expert in first century Judaism and has written standard scholarly works on Jewish history. He has applied this background to thorough analyses of both Jesus and the Apostle Paul.

While Sanders’ work on Paul has a great many detractors, his Jesus and Judaism published in 1985 remains a seminal text in the field. In this book Sanders shows how the Gospels’ portrait of Jesus fits very plausibly into what we know of various movements in Judaism in the period before AD 70 (what is known as Second Temple Judaism). In particular, Sanders places Jesus within a movement in Judaism which longed for a new temple and a new age of God’s presence in the world. This hope for a renewed Israel drove Jesus into conflict with the existing temple authorities in Jerusalem and ultimately led to his death.

Other important scholars of the contemporary Third Quest include Ben F. Meyer, Marcus J. Borg, John P. Meier, James Charlesworth, Norton Thomas Wright (Tom Wright) who is also the Bishop of Durham, Sean Freyne, John Dominic Crossan, Graham Stanton, Gerd Theissen, James Dunn and Richard Bauckham. These scholars differ on plenty of things—this is not a univocal movement—but the shadow cast by the work of Martin Hengel and Ed Sanders can be seen throughout.

Overconfidence never bodes well for scholarship and experts must always remain open to new evidence, but there is little doubt that the search for the historical Jesus is today on its surest footing since Saint Luke wrote: ‘I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning’ (Luke 1:3). To quote James Dunn (University of Durham), someone rarely given to overstatement.

| It has now become possible to envisage Jesus, as also ‘the sect of the Nazarenes’ … within the diversity of late Second Temple Judaism in a way which was hardly thinkable before. This breakthrough has been accompanied and reinforced by other important developments … In short, it is no exaggeration to say that scholarship is in a stronger position than ever before to sketch a clearer and sharper picture of Judaism in the land of Israel at the time of Jesus and as the context of Jesus’ ministry. |

Dr. John Dickson is a Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University (Australia)