Christians who voice ethical opposition to Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell research have often aroused sentiments of frustration and scorn in their fellow citizens. Such views have been presented as scientifically ignorant and heartless impediments to the development of therapies for the sick. Yet the ranks of those who oppose ES cell research include believers and non-believes alike – noted scientists, politicians and doctors, as well as members of the disabled communities and the supposed beneficiaries of the research. So what is going on?

In this article I would like to present a summary of the arguments that are used in opposition to destructive embryo research and ES cell research, as well as a critique of those in favour. I hold my views to be logical and scientific, as well as reflecting my ethical standpoint. I do this not only to explain my position, but also in the hope that as community discussion of this matter becomes more sophisticated, ethical decisions will be better informed. Ultimate decisions by our society may not change, but at least we will know that they have been made in light of the facts involved.

I recognise that there are many views on this topic, even amongst Christians, but I will give you my views and explain my reasoning. One problem with a topic such as stem cell research, however, is that in order to understand the ethics, we need first to understand the science.

I recognise that there are many views on this topic, even amongst Christians, but I will give you my views and explain my reasoning. One problem with a topic such as stem cell research, however, is that in order to understand the ethics, we need first to understand the science.

I will therefore start with a brief biology lesson, followed by a discussion of the science. We will then consider the various aspects of the public debate in Australia both for and against stem cells before finally examining the ethics.

Biology

Human conception begins with fertilisation of an egg by a sperm, creating a single-celled organism called a zygote. From this point, development is a continuum through pregnancy and childhood to adulthood. All the genetic material (DNA) required for full maturity of the human being is present in the zygote. Therefore in embryological terms, at conception, we have a member of the species homo sapiens.

First cell division occurs within 24 hours of conception, and cellular division continues while the embryo travels down the fallopian tube towards the uterus. At day five or six, the basis for the developing baby and placenta, a blastocyst (a hollow ball of cells with an inner cell mass) is formed.

Implantation begins at the end of the first week, when the embryo attaches to the uterine wall and the mother’s blood supply starts to nourish it. This doesn’t always occur successfully, in which case an early miscarriage is said to have taken place.

There is dramatic development over the next six weeks, and by week seven the embryo measures 1.3 cm in length and all essential organs have begun to develop. After eight weeks we start to use the term foetus instead of embryo, but clearly even while still at the embryo stage, an enormous amount of development has taken place. We are dealing with a growing human being when we talk about embryos.

This point is no longer contested since the last legislative debate in Australia. Informed observers accept that we are dealing with embryonic humans. It is now a matter of how we are to treat them.

Human embryos in the laboratory

Human embryos were first created and grown in the laboratory as part of research, which led to the development of assisted reproductive technologies. In 1978 Louise Brown, the first test tube baby, was born in the United Kingdom. More than three million children have been born from in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) around the world since then.

IVF was originally intended as a medical treatment for couples who were unable to conceive naturally, and it was a wonderful development for those suffering from medical infertility. Services have been greatly supplemented since then, but despite all the advances, success rates have always been low. Those running IVF clinics obviously want to do everything they can to help infertile patients, and in attempts to improve the success rates, several practises have developed.

Clinics generally encourage couples to allow the creation of as many embryos as possible after egg collection from the woman’s body. Egg collection is an invasive and expensive procedure with the potential for serious side-effects. You don’t want to do it more than you have to. But obviously, the more times you place an embryo in the womb, the better the chance of a pregnancy developing. There is no formula to accurately predict how many embryos are needed to produce one live birth, hence many clinics suggest the more embryos the better. Just in case you need them.

When the couple have the number of children they want or stop treatment for another reason, they may find that they have surplus embryos. These often represent an unforeseen ethical problem for the parents. It is thought that there are hundreds of thousands of frozen excess human embryos around the world at this time.

Consider the situation as it has developed: scientists could see that the number of surplus embryos was adding up. Many questions concerning early human development remained unanswered. Moves were made to allow experimentation on human embryos in some countries. It is a mark of the special status human embryos hold in our community that destructive research on embryonic humans is still only allowed up to fourteen days of life and requires legal approval.

In the first instance, a lot of the experimentation was aimed at improving assisted reproduction techniques, but then in 1998, human embryonic stem cells were isolated.

Stem cells

There are two things that make stem cells special – they can turn into any type of tissue in the body and they can keep replicating indefinitely.

Scientists are excited about the potential use of stem cells in combating diseases for which we currently have no cure, diseases which involve death of tissue which doesn’t regenerate, like spinal cord problems, heart attacks, different types of blood disorders, brain disorders like Parkinson’s Disease, diabetes, and many others. This is a very promising area of medical research, often called ‘regenerative medicine’, to which no sensible person objects.

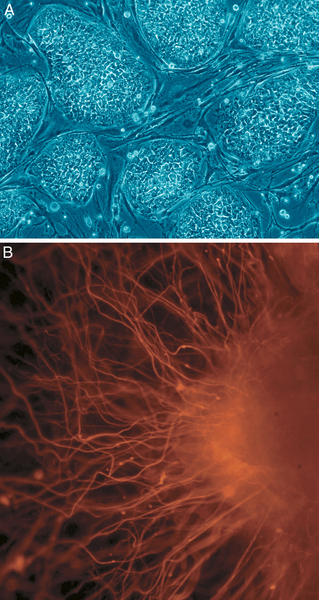

Now many people are confused about stem cells because they don’t realise there are two types, depending on from where they are collected. Firstly there are embryonic stem cells, collected from the inner cell mass of a six day old blastocyst, a process which kills the embryo.

The second category is adult stem cells, a slightly confusing term as they are collected not just from adults, but also children, placenta, cord blood, in fact any source other than embryos. The harvest of these stem cells does not cause any lasting damage to the person from whom they are collected.

So far research has been very encouraging for adult stem cells in many areas, with progress being made in treatment of over seventy diseases

Those who value human life from fertilisation immediately recognise an ethical difference between these two types of stem cells, as one involves death of the developing human from which it is harvested, while the other causes no lasting damage.

The plan for using stem cells in therapy is that once they are grown in the laboratory, if they could be turned into the type of cell you needed for a particular patient, you could inject them and repair the problem – heart cells for a damaged heart, nerve cells for a damaged spinal cord etc. So far research has been very encouraging for adult stem cells in many areas, with progress being made in treatment of over seventy diseases. There are problems with research into embryonic stem cells as they can turn into cancers (teratomas) when injected into animals in treatment trials. Despite this problem, some scientists want to persist with the research as ES cells are easier to harvest than adult stem cells and may be more flexible. Obviously no human research will be approved until the cancer problem is overcome.

Opposition to embryo destruction has led to some creative thinking which has led to the discovery in late 2007 that skin cells can be reprogrammed to function like ES cells. These cells, called Induced Pluripotent stem cells (IPS cells), are produced without the use of cloning, human eggs or the destruction of human embryos. They look the same and act the same as ES cells.

Those opposed to ES cell research have no ethical objection to regenerative medicine that uses adult stem cells or IPS cells. The main reason they object to ES cell research is because it involves the destruction of embryonic humans. But there is another ethical problem they foresee in ES cell therapy, that of cloning.

Cloning

Obviously, the aim of research on ES cells is a worthy one – the development of therapies to help sick patients. But to explain the ethical dilemma, imagine this scenario. Suppose I sustain an injury to my spinal cord so that I can no longer walk. In the future doctors may decide to treat me with ES cell therapy. However, if they take one of those frozen embryos in an IVF laboratory and grow it up into a blastocyst, harvest the ES cells, turn them into nerve cells and inject them into my neck, my body would reject them. This is because my body would recognise that they have different DNA (genetic material) to my cells.

To overcome this rejection problem it has been suggested that instead of using a frozen excess embryo, we make an embryo clone of me. (A clone is another human with the same DNA). This would be done by taking the nucleus out of a human egg, replacing it with the nucleus from one of my cells, for example a skin cell, and stimulating it to replicate. It would then be grown to the blastocyst stage, at which time the stem cells (with my DNA) could be harvested, thus killing the embryo. This time my body would accept them as they have the same DNA as my other cells. This type of cloning is usually called ‘therapeutic cloning’, as it is hoped that therapies will be developed from it. It is also called ‘cloning for research’. (Note that this procedure is not yet possible).

Even when cloning technology is restricted to therapeutic purposes, it remains ethically troubling for many people

But there’s a problem. Remember Dolly the sheep? (Cloning to create a live birth is called ‘reproductive cloning’). The technology used to create her is exactly the same as that used in therapeutic cloning. If doctors had decided not to use the cloned blastocyst of me to get ES cells, but instead transferred it to a woman’s womb, it could technically come to birth as my clone.

There is no doubt that our community generally sees reproductive cloning as wrong. There are many ethical reasons for this, including confusion of family relationships. Even when cloning technology is restricted to therapeutic purposes, it remains ethically troubling for many people. The problem is that the process involves creating human life expressly for the purpose of killing it. In some ways this is more abhorrent to those of us in the opposition camp, than reproduction, where at least the clone is given a chance of life by transferral to a womb. There is also a concern that the demand for human eggs for the cloning process would make financially needy women vulnerable to coercion to donate for large amounts of money. (Currently some IVF clinics offer thousands of dollars for donated eggs).

Further, according to opponents of destructive embryo research, none of this is necessary. You can see that it is possible to have stem cell therapies developed with no ethical problems by using adult stem cells and now we also have the promise of IPS cells.

The ethics of the public debate

The centre of the stem cell debate is disagreement over whether embryonic humans should be used for destructive research. The disagreement can most easily be understood when we consider different ways of defining the embryo.

1.The biological definition

Eminent embryologist Ronan O’Rahilly has no doubt that in biological terms we are dealing with a human being from the time of fertilisation. ‘Although life is a continuous process, fertilisation … is a critical landmark because, under ordinary circumstances, a new, genetically distinct human organism is formed when the chromosomes of the male and female pronuclei blend in the oocyte (egg).’ From the time it is created, the embryo is a unified, unique, dynamic, self-directed whole, not just a collection of cells. There is evidence that organisation exists from the first cell division.

Opponents of human ES cell research reason that if a human being exists from the time of fertilisation, it is unethical. This is because the harvesting of the stem cells destroys the blastocyst.

While the foremost promoters of this position in Australia tend to be the churches, it is not a religious divide. Other groups such as those interested in human rights also oppose ES cell research and the Greens are often on board on grounds of their opposition to manipulating the human gene pool.

Destructive research on human embryos contravenes years of human rights declarations, which since World War II have been designed to protect the welfare of human research subjects. The Council of Europe Biomedicine Convention from 1997 specifically prohibits destructive research on human embryos and the creation of human embryos for research. It also prohibits human reproductive cloning. The United Nations released a statement on cloning in 2005 that opposed all forms of human cloning.

if there is no doubt biologically that the human embryo is just that, human, from the time it is created, how is their destruction justified?

Opponents of destructive research on human embryos do not think they are risking the loss of any medical therapies. They regard the success of adult stem cell research and the discovery of IPS cells as evidence that regenerative medicine can develop without using ES cells. Generally it is suggested that the excess embryos in IVF clinics be adopted by infertile couples or allowed to die undisturbed. Opponents would also like to see a tightening of safeguards to prevent further accumulation of excess human embryos. Use of the ‘spare’ embryos has meant that a market for human embryos has developed which has, predictably, led to legislation allowing the creation of more embryos for destructive research. So, if there is no doubt biologically that the human embryo is just that, human, from the time it is created, how is their destruction justified?

The answer lies in the philosophical definition.

2. The philosophical definition

Protagonists of destructive embryo research have suggested that protection is only due to human persons, and that personhood is not achieved merely on biological grounds. The idea of personhood was first introduced into the beginning of life, ironically, by a Christian, Rev Joseph Fletcher, an Episcopalian minister who in the 1950s was looking for a way to allow abortion, which many Christians at that time saw as an act of compassion – a long story which we will have to leave for another time. The concept of personhood has been around for a long time, and arguments vary widely as to when personhood begins.

Grounds have been put forward for the commencement of personhood at various points including implantation, when the one-week old embryo has attached to the mother; birth; and several weeks after birth, a position espoused by philosopher Peter Singer. The latter argument justifies infanticide on the grounds of newborns being non-persons. Alternative theories argue that there are certain attributes, which must be possessed by the developing embryo before it can be called a person.

The argument that has influenced many countries’ treatment of human embryos was that put forward by the United Kingdom’s Warnock Report (1984) which, while acknowledging that embryonic humans should have a special status, decided to avoid answering the question of when life or personhood began. Instead it discussed how the embryo should be treated. The Warnock Committee approved research up to 14 days (the time when the primitive streak was visible in the embryo), since ‘this marks the beginning of individual development’.

Proponents of ES cell research point to other social policies that imply the same notion (that the nascent human does not deserve protection): access to elective abortion, the use of post-conception contraceptives and the destructive research already occurring in IVF clinics. The high rate of natural embryo implantation failure is also used in support of this position.

It is also argued that the surplus frozen embryos are going to die anyway, so we might as well get some benefit from them before that happens. This position relies on the philosophical theory of consequentialism – that it is only the consequences of our actions, not the actions themselves, which determine right from wrong. By suggesting that the moral interests of the surplus embryos are trumped by the needs of the sick who would benefit from possible therapies developed, some have argued that it is unethical NOT to use the embryos for research.

3. The middle position

In the initial Australian public debate on stem cells in 2002, the most common view in the community was a variation of this, ie that ES cell research is ethical so long as only surplus embryos are used and informed consent is obtained from those for whom the embryos were created. While the loss of the embryos was seen as regrettable, the benefits of the research justified their use.

saying you might as well use unwanted embryos for research depends on the idea that the human embryo is not a human person, deserving of protection

Note that there are several unspoken assumptions in this argument. The first is that the ends can justify the means, especially if the ends are great health benefits (consequentialism again), the second is that there are no ethical problems in destroying embryos on purpose rather than just letting them die, and there is even a suggestion that those who raise ethical questions may lack compassion in denying many who are suffering debilitating or life-threatening illnesses the chance of a cure. But saying you might as well use unwanted embryos for research depends on the idea that the human embryo is not a human person, deserving of protection.

Personhood

I think it is worth pausing here to look a bit closer at the idea of ‘personhood’. The dictionary defines person as a living human being.

Fletcher’s definition was driven less by scientific discovery and more by the political debate around abortion. If the embryo was not fully human then it would be much easier to justify abortion.

He argued that what sets humans apart from other animals is their possession of reason. This is what grounds human dignity and, he said, is signified by the term ‘person’.

He goes on to argue that if the human embryo is not a human person then it does not merit legal protection. His approach is based on the work of the English philosopher John Locke.

Therefore, along with newborns, he excluded human embryos and foetuses, but you would also have to exclude a mentally disabled adult and, technically, a perfectly normal adult who was asleep or unconscious – because their reasoning is also latent.

Fletcher’s definition focused on the actual powers that someone could display, explicitly excluding even newborn infants from personhood. For his definition, the possession of human nature, with the latent ability to reason, was insufficient. Therefore, along with newborns, he excluded human embryos and foetuses, but you would also have to exclude a mentally disabled adult and, technically, a perfectly normal adult who was asleep or unconscious – because their reasoning is also latent.

So in response to this argument regarding personhood, many people, and Christians especially would suggest that surely this is an unacceptable way to decide which humans deserve protection in our legal system. Traditionally those who are vulnerable are seen to be in more need of protection rather than less. Which suggests that it is important that we stay with the standard definition of person – ie a living human being – if we are discussing personhood. Christians are concerned that arguments about personhood are merely a foil aimed at political expediency – in this case, to allow destruction of human embryos for research.

Other ethical concerns

As in many of our public debates, community discussion regarding the benefits or dangers of ES cell research has been superficial and ill-informed. Exaggerated claims from scientists and the media regarding the state of ES cell research has led to unrealistic expectations on the part of many citizens. While this is a perennial problem in medicine, where any break-through in a lab becomes a headline for a cure, even some stem cell scientists admitted that in their enthusiasm they may have overestimated what could be done. ‘Dumbing down’ of the debate by newspapers, so that it was presented as a simple choice between benefits for the disabled versus unwanted embryos, meant that the distinction between adult and embryonic stem cells was completely lost for many Australian citizens.

Summary of legislation in Australia

The initial legislation passed in 2002 allowed frozen excess ART embryos to be used in destructive research, under licence (some stem cells lines have been produced). The original legislation required a review within three years, which led to the Lockhart Report in 2005. Legislation passed in 2006 allowed, among other things, human cloning for research (therapeutic cloning) but not for reproduction. Once again, a review will be completed within three years to consider whether the legislation should be altered again.

The Christian approach

For all ethical dilemmas, Christians have a moral compass derived from the Bible. There is no key verse that tells us when personhood begins. The Christian argument for personhood commencing at conception is put together by combining a number of themes running through the Bible.

The Bible makes the link between conception and birth in many places. Jesus’ presence on the earth is described as beginning when the virgin conceived through the Holy Spirit, and the incarnation is a powerful reminder of the status embryos hold in the eyes of God.

Scripture describes the relationship people have with God when still in the womb, such as during our formation. Psalm 139:13 – 16 ‘for you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb’.

At the very least, the concept of being made in God’s image has profound implications for the value to be placed on human life; the protection and care it deserves, and the gravity of interfering with it

The Bible recognises that all human beings bear the image of God and therefore deserve to be treated with respect. It is this ‘image of God’ status that suggests humans have unique value – value that is inherent, and not therefore dependent on any particular capacity such as the ability to reason. There is no doubt that the unborn human is recognised in the Bible as capable of a relationship with God in a way that no other creature can claim. At the very least, the concept of being made in God’s image has profound implications for the value to be placed on human life; the protection and care it deserves, and the gravity of interfering with it. This might do nothing to convince those who don’t believe in God, but it should help them to understand where Christians are coming from in this debate.

The Bible also teaches that the end does not justify the means. It refutes the notion that we should do evil that good may result. And throughout the Bible is the consistent thought that a person’s actions do count, they have meaning. What a person does, matters in itself. Christian ethics recognise some biblical rules, to be observed in the context of Christian virtue (a modified virtue ethic). The sixth commandment says we should not kill innocent human beings, regardless of the consequences.

Conclusion

The basic issue at the heart of this debate remains the moral status of the embryo. What are our options?

It is now known that it is possible for ES cell-type research to proceed without the destruction of human embryos, through use of IPS cells. This discovery is not completely unexpected, because in the history of western science, ethical limits have led to imaginative solutions rather than remaining barriers to discovery. However, many scientists have recoiled from suggestions that legislation allowing destructive human embryo research be overturned. So how do we find consensus as a community? I would suggest that it is not possible. In the end, the moral status of the embryo is not a fact, but a value. We will each of us decide that which is valuable to us on the basis of our worldview.

Those who would pursue destructive embryo research are considering consequences only, those opposed are concerned with the act itself – there are some things you should just never do. The two parties are passing like ships in the night. They will never meet because they are talking about different things. In a pluralistic society we cannot just ignore the people we disagree with, we need to consider all the different views in our community when we are making decisions. Where there is no consensus, we take a vote. He with the most votes wins. Personally I am happy with this, on one condition – that those who vote are fully informed regarding all the facts, not just some of them.

Dr Megan Best is a medical practitioner and a bioethicist.