Last week’s Met Gala in New York raised some eyebrows, focusing, as it did, on the connection between high fashion and the church. Titled “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” it drew the usual cavalcade of glamorous celebrities but this year they were wearing gowns inspired by saints, popes and religious iconography.

Commentary was divided on whether this was merely a celebration of the “complex and sometimes contested” influence of religion and liturgical vestments on fashion, as the curator of the accompanying display would have it. Or a gaudy, disrespectful lampooning of Catholic doctrine and history.

What does the church stand for: self-sacrificial giving to the poor? Earthly Power or humility and vulnerability?

Kim Kardashian, resplendent in a body-hugging golden metallic Versace dress emblazoned with crosses, was bound to divide opinion, even if some, such as columnist Kevin McKenna could, cheekily, interpret her dress as a curvaceous communion cup!

The Vatican sent some precious cargo to be displayed at the exhibition. Ornate objects and garments, some of which had never previously left the Vatican archives, including the nineteenth-century tiara of the longest serving Pope, Pius IX. The triple crown, as it is called, made up of 18,000 diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds and pearls, arrived with its own bodyguard.

Jesuit priest, James Martin, who attended the ball, took Vanity Fair on a visit to the Met’s exhibit a few hours before the celebrities took over. The magazine records a fascinating aside from him as he pauses before Pius’ triple crown. While admiring the beauty of the objects in front of him he also acknowledges, “It’s a long way from the carpenter in Nazareth”, noting that the current Pope Francis, famous for his austerity, has eschewed such ostentatious clothing.

It’s a fascinating comment, summing up two sometimes conflicting narratives around what the Church stands for? Do these lavish trimmings represent an attempt to experience and worship the divine, or are they obscene objects of wealth? What does the church stand for: self-sacrificial giving to the poor? Earthly Power or humility and vulnerability?

For the last three years, my colleagues and I at the Centre for Public Christianity have been researching and creating a historical documentary titled, For the Love of God: How the Church is Better and Worse than You Ever Imagined, to explore these very questions.

Our findings? Well, it’s complicated.

The carpenter from Nazareth referred to by Fr James Martin, inspired his early followers to take seriously his call for self-sacrificial service of those in need, and it turned the ancient world on its head. When Christianity burst onto the Greco-Roman scene in the first century, Charity, of the sort we know today, was non-existent and unimaginable.

By the fourth century, those charitable efforts were causing consternation. The pagan emperor Julian was scandalised by the Christian’s care for not only their own poor but “ours as well”. Concerned that “the hated Galileans devote themselves to works of charity”, he was worried the Christians were going to take over the empire by the stealth of their good deeds.

And yet our filming also took us to sites where, centuries later, corrupt church leaders, drunk on power, garnered astonishing personal wealth (and sometimes mistresses); violently establishing their rule while utterly neglecting their sacred duty to the poor.

In the midst of these jarring historical contradictions, the most compelling and moving stories we encountered were of the lives of those who clearly “played in tune” with the radical teachings of Jesus.

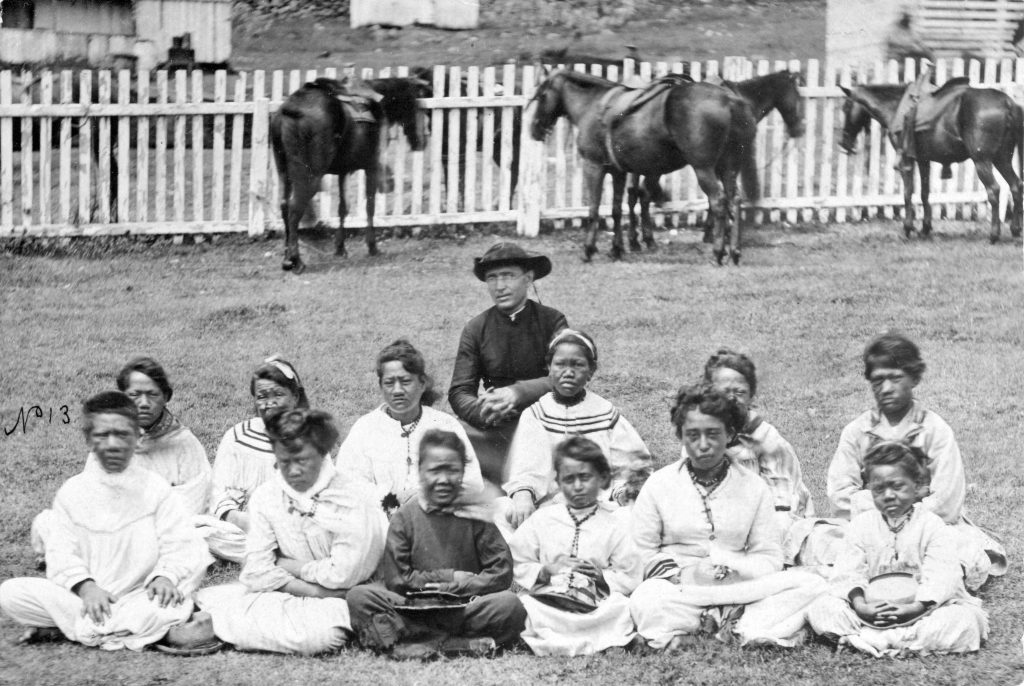

One story we tell in the documentary is of Father Damian De Veuster, a Belgian priest who became an inspiration to both Gandhi and Mother Theresa. Sent to a leper colony on the remote Hawaiian island of Molokai in 1873, where people were forcibly quarantined in what was known as the “sick paradise” and left to rot and die, Father Damian set about restoring dignity and purpose to that abandoned and wretched community.

He built houses and orphanages; served as a teacher, gardener, and magistrate; introduced music and a sense of meaning back into their lives. He followed the example of Jesus, who never hesitated to touch lepers. He literally entered into the pain of others, eventually contracting and dying from the disease himself, joining the ranks of those he came to care for.

Gandhi, who was a serious critic of Christianity, once said, “The political and journalistic world can boast of very few heroes who compare to Father Damian,’ continuing, ‘The Catholic Church, on the contrary, counts [them] by the thousands. It is worthwhile to look for the sources of such heroism.”

There’s no doubting the church has been a mixed bag over the centuries and there is much in that history that is indefensible. But at its best moments, impelled to follow the hard, slow path of charitable work for those in need, the church has made, and continues to make, a massive contribution to a kinder, more compassionate world.

Simon Smart is Executive Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and co-presenter of “For the Love of God: How the Church is better and worse than you ever imagined” which is in cinemas in limited release.